6.4. Survey Results: Early Agropastoralists Period (3300BCE - AD400)

This temporal period covers the calendar years 3300 BCE through AD400, incorporating a time that includes dramatic changes in the region from the Terminal Archaic through the Late Formative following the Titicaca Basin chronology. As was described in Chapter 3, during this time period the sweeping changes that occurred in the larger region are linked at the Chivay obsidian source through evidence of intensification of obsidian production, the establishment of regular llama caravan traffic linking far-flung parts of the south-central Andean highlands, and a dynamic political environment in the Titicaca Basin consumption zone that appears to have influenced behavior at the source.

In the Terminal Archaic, distinctive economic changes that were accompanied by social and political developments were brought about in a broad suite of transformations that appear to have been co-evolutionary. Briefly, these changes began with transitional or low-level food production (Smith 2001) in the form of animal husbandry and a greater reliance on seed-plants. These changes were also associated with greater evidence of sedentism (Aldenderfer 1998;Craig 2005) and these settlements were linked through expanding interregional networks that appear to have interfaced through regular llama caravan transport (Browman 1981;Dillehay and Nuñez 1988). By the end of the phase described here as "Early Agro-Pastoralists" a number of regional centers in the Lake Titicaca region emerged during the Late Formative (Stanish 2003: 137-164) that were controlled by a socio-political elite in a socially complex, ranked society. The influence of these powerful political and religious elite were most evident at the primate centers of Late Formative Tiwanaku and Pukara, centers that grew in influence through, some have argued, the harnessing of labor to produce food, build monuments, and control interregional exchange.

In this research, features used to differentiate the Early Agropastoralists period occupations from the preceding Archaic Foragers and from the later Late Prehispanic periods are comprised by evidence from artifactual data and settlement pattern data. With the beginning of the Early Agropastoralists period one can expect the reliance on herding in the Upper Colca to have changed the settlement pattern in the direction of areas that are suitable for herding, in particular reliable water sources and bofedales for alpacas. The Series 1-4 projectile points (except 4c and 4e) are diagnostic to the Archaic Foragers period and so components associated these projectile points are therefore pre-pastoralist by the definition used here. A ceramics style termed "Chiquero" is thought to be diagnostic to the Formative Period based on surface distributions in the main Colca valley (Wernke 2003), but in the course of the 2003 Upper Colca fieldwork, ceramics in the style similar to Chiquero persisted into Middle Horizon period strata in one test unit in Block 3, suggesting that this ceramic style persisted in use in the higher altitude regions of the Colca. Thus, the presence of sand-tempered, unburnished ceramics can be used to differentiate the Early Agropastoralists period from the preceding preceramic time period, but not the Middle Horizon end of the Early Agropastoralists period in the Upper Colca. The end of the Early Agropastoralists period with the onset of the Titicaca Basin Tiwanaku period (AD 400) is more difficult to differentiate because the pastoral economic basis of the periods in the Upper Colca are not significantly transformed, and therefore the settlement pattern may be largely unchanged.

Diagnostic ceramics of the Middle Horizon, Late Intermediate Period, and Late Horizon have been described comprehensively by Wernke (2003) and therefore the presence of these ceramics is one way to differentiate certain components as "Late Prehispanic".

Based on the site classifications used for the pre-pastoralist Archaic, the Early Agropastoralist sites in the Upper Colca are considered here in terms of (1) residential bases, (2) logistical camps, and (3) isolates. These site groupings have analogs in the settlement pattern of modern pastoralists, where residential bases consist in distributed estanciasof varying sizes with adjacent grazing areas where permanent or seasonal residence is established, and logistical camps or "herding posts" that consist of regular travel stops during travel between estancias and other settlements (Nielsen 2001: 193-196;Tomka 2001). These types correspond with "main residences" and "herding posts" described with archaeological correlates by Nielsen (2000: 478-482).

|

Type |

Description |

Expectations |

|

Residential Base |

Long term occupation or regular reoccupation by several adults and sometimes children. Corrals with soil of compacted dung. Formalized use of space apparent in task areas and artifact distributions. Regularly distributed across land with available grazing areas and a reliable water source. |

Variety early vessel forms, including large cooking vessels. Possible correlation between low diversity in lithic raw material types and long term occupation due to relatively low mobility. Site maintenance activities (cleaning, dumping) and designated activity areas expected. |

|

Logistical Camp |

Short term but regular reoccupation by special task groups. Smaller and more uniform site characteristics. |

Few large vessels, possible caching of implements for reuse. Relatively high assemblage diversity in both lithic types and ceramic pastes. Less evidence of site maintenance due to multiple short-term occupations. |

|

Herding shelter |

Small occupation for night or day use with windbreak and view of grazing areas. |

Windbreak with view, possible animal bone and some lithic debris, possible hearth. No corral necessary for short occupations. |

Table 6-47. Classifications for Early Agropastoralist components of sites

Criteria used for identifying pastoral camps were available in the course of this study (Figure 6-48). Unlike the Upper Colca area, some of the ethnoarchaeological data used for constructing these categories come from regions, like eastern slopes of the Andes in Bolivia (Nielsen 2000: 480-483), that had low site reoccupation and spatial redundancy due to an abundance of suitable pastoral camp areas. Ethnoarchaeological evidence suggests that short-term herding posts with little site structure but many reoccupation episodes will often contain many hearths with associated overlapping middens that result from groups moving the hearth facilities to avoid debris from earlier occupants (Nielsen 2000: 480-483).

Pastoral bases and herding posts are characterized by extensive but shallow refuse discard. Bases may contain greater density contrasts in refuse discard because of longer term occupation and site maintenance activity, and areas around rich resource patches are likely to contain "large and dense archaeological sites resulting from multiple, non-contemporaneous, partially overlapping, and perhaps functionally diverse occupations" (Nielsen 2000: 482-483). Short term caravan stops do not necessarily contain corrals, as camelids do not require corralling every night.

Nielsen (2000) observes that short term herding posts (logistical camps in the typology used here) and shelters appear to prioritize the following features, beginning with the well-being of the caravan animals:

- Grazing opportunities.

- Water for the herd.

- Shelter from the wind.

- Other human concerns such as hunting opportunities and proximity to the residences of exchange partners.

Herders will take advantage of existing structures, such as wind breaks and sometimes existing hearths, but they virtually never construct new features in their short term occupation of overnight camps (Nielsen 2000: 452).

6.4.1. Block 1 - Source

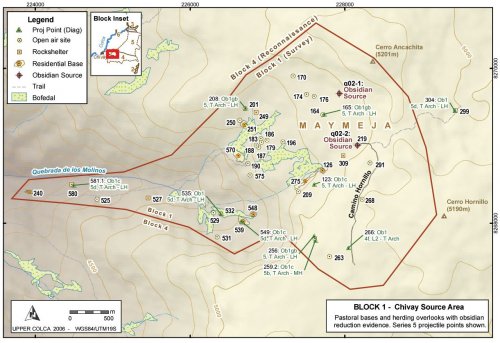

The Early Agropastoralist period in the Maymeja area of the Chivay source appears to reflect to major foci of economic interest in the area: (1) obsidian intensification, and (2) the exploitation of the rich pasture from the bofedal that lies in the western half of Maymeja. The strongest manifestation of settlement redundancy in the Maymeja area was at a handful of residential bases that were utilized by pastoralists over the millennia.

The most telling patterns in lithic production evidence come from contexts that differ from the expectations derived from purely pastoralist settlement patterns. For example, there is evidence of substantial settlement in an area with an obsidian workshop that is relatively unused today by the herder that dwells in Maymeja with over 200 head of alpaca. One explanation for this pattern is that the earlier settlement pattern was the result of obsidian procurement and production occurring at the quarry pit on the south side of Maymeja. That is, pastoral land use patterns are largely redundant in the region since approximately 3300 BC, but despite this redundancy there was variation from the purely pastoral pattern that suggests a Formative Period economic focus on obsidian production.

Block 1 Obsidian procurement features

One of the biggest challenges of working at the Chivay source during the 2003 season was evaluating the evidence for the incentives that drove ancient people to excavate a quarry pit to acquire larger nodules of obsidian, and the evidence for who was responsible for the quarrying work. Presumably, the earliest visitors to the Chivay source had the first pick of the largest and most homogeneous nodules, but over the millennia the source would be relatively depleted as compared with the initial abundance during early human visitation sometime in the Early Holocene. A quarry pit [Q02-2] that was encountered in the south-east quarter of Maymeja is evidence that investing labor in excavating for obsidian was indeed worthwhile.

At some sources, for example in the upper reaches of the Alca source as described by Rademaker (2005, pers. comm.) large blocks of obsidian of variable quality are found littering the surface. At lower elevations at the Alca source, and closer to large settlements, small cavities and tunnels were excavated to retrieve obsidian (Jennings and Glascock 2002).

Q02-2 "Quarry Pit"

The upper area of Maymeja, as well as the eastern flanks of Cerro Hornillo, are blanketed with small fragments of obsidian that appear as lag gravels among the tephra soils of the area (Section 4.5.1). In particular, flows and large nodules of obsidian are exposed through erosion in some areas, which suggests that underneath the tephra are larger nodules, but one has to excavate for them. On the north side of Maymeja, in an area heavily eroded by glaciers, a flow of obsidian [Q02-1] was observed but it contained vertical, subparallel fractures and was generally not suitable for tool production.

At the same altitude as this natural flow, but 700m to the south and across several moraines is a quarry pit [Q02-2] located in an area where the ashy soil was particularly light-colored. Similar open-air obsidian quarries have been described in central Mexico as "doughnut quarries" (Healan 1997) and "extracción a cielo abierto" (Darras 1999: 80-84). See Section 7.4.1 for further details on this quarry pit.

The coordinates of the Q2-2 pit are 71.5355° S, 15.6423° W (WGS84 datum), and it lies at 4972 masl. Around this quarry pit many small obsidian nodules in a depression were encountered that were typically < 5cm in size, but a few were closer to 15cm on a side. There is a smaller mound of sandy soil and small fragments of obsidian inside the larger quarry pit, suggesting that someone has attempted to further excavate the quarry pit in the more recent past.

Figure 6-45. Testing at Quarry Pit Q02-2 with 1x1 test unit Q02-2u3. Snow remains in the pit.

During the 2003 field season a test unit was placed in the debris pile immediately downslope of this quarry pit. The quarry pit and the test unit results are described in more detail in Section 7.4.1 and a brief discussion of ancient quarrying methods can be found in Section 8.3.2.

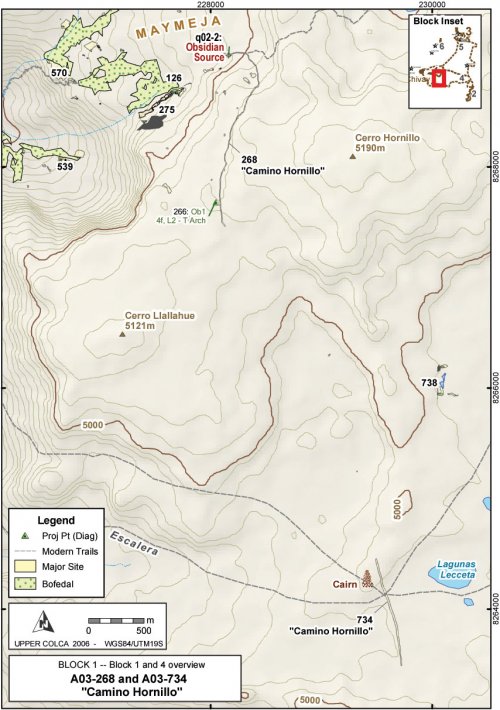

A03-268 "Camino Hornillo"

Departing from the quarry, a prehispanic road was identified that is 3-4m wide and is cleared of all but the largest rocks. This road [A03-268] departs the Maymeja area towards the south, following the route with the lowest gradient out of the volcanic depression, and avoiding difficult talus areas. As the road is defined by being swept free of rocks, the road is difficult to follow where it enters areas consisting only of sandy soil with no rocks to define its edges. In 2003 two sections of this road were mapped for a total of 3 km, and based on observations it can be described as of the " Cleared Road type: … systematically cleared of all stones or other debris" (Beck 1991: 75-76). While the soft pads of camelid feet negotiate rocky terrain with relative agility, loaded caravan animals generally travel on cleared roads and trails. Nielsen describes caravan routes in the open altiplano as "wide (4-10 m), straight, and free of vegetation, but lack[ing in] any improvement" (Nielsen 2000: 447). By these criteria, the route encountered at the Chivay source is relatively narrow, but it is roughly twice the width of a single-file path.

Figure 6-46. A03-269 and A03-734 "Camino Hornillo" and modern trail system.

No ceramics or architectural features were found in association with this road, and the only temporally diagnostic artifact identified was an obsidian type 4f projectile point diagnostic to the latter part of the Late Archaic and the Terminal Archaic. The construction of the swept road is being interpreted here as Terminal Archaic - Early Formative in age because it is associated with a workshop that contained radiocarbon dating to that time, and this date is further supported by the presence of the Terminal Archaic projectile point along the route.

At 4 km from the quarry pit, the southern segment [A03-768] of Camino Hornillo meets the Escalera route, a large trail that appears to have been a major thoroughfare for pack trains climbing steeply out of the Colca Valley to the puna and off towards the East-South-East (the direction of Lake Titicaca). A relatively large cairn or apachetastands on top of a boulder just northwest of this significant intersection, probably a guidepost marker in an otherwise open and featureless expanse.

|

Figure 6-47. Apacheta (cairn) close to junction of the Escalera route with Cerro Hornillo. |

While there were no artifacts associated with this cairn to facilitate dating its construction, the practice of contributing stones to cairns by passersby suggests that large cairn have some antiquity (Nielsen 2000: 447-448, 489). These features are associated with ritual activity in a variety of cultures worldwide including the North African Twareg (Rennell 1966 [1926]: 293), Tibetans (Trinkler 1931: 72), and other Himalayan highland groups (Valli and Summers 1994: 11). While cairns are abundant on an adjacent pass at Patapampa along the principal Arequipa highway to the Colca, those cairns have become a focus for tourist activity and many are the result of modern construction by passing tourists.

Today, the route of the modern Chivay - Arequipa highway has shifted traffic to Patapampa and around south side of Cerro Huarancante, and as a consequence these more ancient travel routes long used by pack animals, see little modern use except by local herders.

Interestingly, Camino Hornillo crosses the Escalera route and continues with the same width and definition in the direction of Nevado Huarancante to the south, as if the role of Camino Hornillo was more than simply a spur on the larger trail network in the direction of the Chivay obsidian source. Beyond the Lecceta-Escalera pass area, the Camino Hornillo [A03-734] begins climbing a hill and disappears again into sandy soil. Due to time constraints the 2003 field season team was not able continue following this road, but the route suggests that there was an objective in the southerly direction beyond the Escalera thoroughfare.

Figure 6-48. Camino Hornillo showing (a) A03-268 and (b) A03-734 segments. Photos were digitally modified to highlight the route in red.

The Quebrada Escalera route (in the southwest portion of Figure 6-46), which is now primarily a narrow footpath, seems to have had varying degrees of historical importance as access route in and out of the Colca. As reviewed in Section 3.2, the ethnographic accounts of caravans arriving into the Colca from the eastern puna are numerous (Browman 1990: 404,416-414;Casaverde Rojas 1977;Flores Ochoa 1968: 107-137). These caravans, by necessity, would have had to take one of the relatively steep routes that go to the north or the south of Nevado Huarancante. The route to the south of the mountain, which is the route taken by the modern highway to Arequipa (constructed in 1947 by Conscripcíon Vial), has steep pitches that would have presented obstacles to caravan transport as does the Quebrada Escalera route. Guillet (1992: 27-28) describes the historical importance of the construction of railroad station at Sumbay in Pampa de Cañagua, because with the railroad travel to the city of Arequipa by mule was reduced from being a one week journey to being a 2.5 day trip. One well-established route between Sumbay and Chivay passed through the Lecceta-Escalera area as it skirted north of Nevado Huarancante and descended Quebrada Escalera into the Colca. In sum, two faint segments are apparent of a road referred to here as "Camino Hornillo" that depart the quarry pit [q02-2] towards the south and arrive at the major travel route represented by the Escalera, but then the route continues southward in the direction of Huarancante. Further study of this road is needed.

Block 1 Reduction and projectile points in the Early Agropastoral period

Consumption patterns in the south central Andes indicate that projectile points are the most frequent artifact type for obsidian, a pattern that becomes particularly strong with Series 5 projectile point production sometime after the onset of the Terminal Archaic circa 3300 BCE An important question in this research is, therefore, "in what form was obsidian leaving the Maymeja zone during a particular time period?"

Part of this question is answered simply by looking at the 2003 projectile point inventory: obsidian Series 5 points are actually relatively scarce in the Maymeja area, and flakes that approach Series 5 projectiles in shape, are not especially common in the collections either (see Table 6-15, above). As will be suggested by the Maymeja excavation data in Section 7.4, distinct groupings of cores and flakes discarded at the workshop suggest that reduction was following a few discrete pathways that might indicate that two trajectories, both the flake-as-core and the flake directly to implement, reduction strategies were occurring at the Chivay source.

Block 1 Early Agropastoralist Settlement pattern

A primary goal of modern pastoralists residing in Maymeja is to guard their flock both during daytime grazing and during the night when rustlers, foxes, and, formerly, mountain lions, are liable to attack the herd (T. Valdivia 2003, pers. comm.). It is evident from regional distributions in the Chivay Source area that during the Terminal Archaic and Formative Period there was a combined interest in herd maintenance with obsidian production. A key feature of the Maymeja area is that procuring obsidian from this zone did not require compromising grazing potential for access to obsidian: both appear to have been available on the southern margins of Maymeja.

Figure 6-49. Block 1 possible Early Agropastoral settlement pattern with Series 5 projectile points.

Residential bases: Several large sites were identified that have been interpreted as residential bases for herders. These residential bases include corrals, possible remnants of residential structures, and site maintenance activity such as the discard of lithics in discrete areas. These bases represent probable overnight camps.

Open air sites: Small sites, consisting typically of a windbreak and a small obsidian scatter overlooking a bofedal, are distributed throughout the Maymeja zone. These small camps, described here as "open air sites" are probable day-use overlooks for herders.

Rock shelters: A number of small rock shelter sites were also encountered in this area. These are typically very small rock shelters, often no more than a small overhang of a boulder or the edge of a lava flow. The shelters commonly contain a small scatter of obsidian flakes, and sometimes cores, at the dripline of the rock shelter.

Miscellaneous other site types: Other kinds of sites include an obsidian quarry pit [q02-2], and Camino Hornillo [a03-268] which is a route leading to the quarry pit from the south.

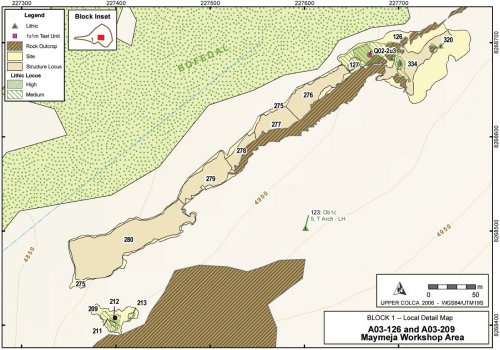

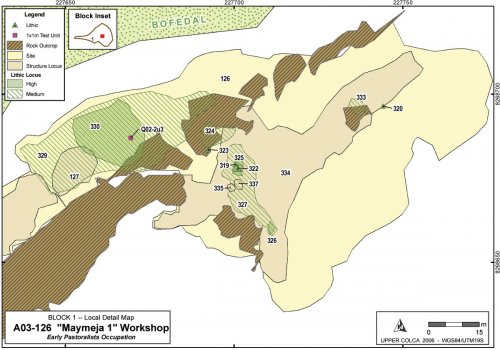

A03-126 "Maymeja 1"

On the southern edge of Maymeja a site was located that contained a dense mound of flaked obsidian, an extensive scatter of obsidian, traces of terracing and wall building, but virtually no ceramics. Dates from a 1x1m test unit [Q02-2u3] placed in the obsidian mound (Section 7.4.2) showed that this site was occupied from at least the Terminal Archaic until the end of the Early Formative.

Figure 6-50. A03-126 "Maymeja 1" workshop and vicinity.

Maymeja 1 [A03-126] belongs to a complex of features that have been divided into an upper site A03-126, and a lower site A03-275 that has some LIP and LH component. This complex is located on the dry southern margins of the Maymeja area where viscous lavas emanating from the Cerro Hornillo vent slope downwards to the northwest into the depression referred to as Maymeja. Subsequent glaciation polished these lavas into smooth banks with excavated depressions that offer adequate shelter in this exposed region. The shelter and abundant sun in this north-facing zone is compensated for by the mountain winds that blow with regularity in the area.

Figure 6-51. View of A03-126 "Maymeja" from north. Terraced area A03-334 on upper level. Test Unit Q02-02 is just right of the orange bucket. Project tents are visible in corral A03-127.

|

(a) |

Figure 6-52. (a) Workshop area of "Maymeja 1" showing proximity of bofedal, (b) Testing Q02-2U3, with the quarry pit [Q02-2] visible among light ash 600m uphill in the background.

The residential base of A03-126 consists of two principal zones that show human modification: (1) the upper area above the polished lava bluffs visible in Figure 6-51, and (2) a lower zone that abuts the bofedal to the north. As the area is almost devoid of ceramics the primary indicators of occupation are lithic scatters of varying density and with highly eroded walls and terraces. The central greatest concentration of flaked stone is the workshop area labeled as a high density lithic locus [A03-330], shown on Figure 6-50.

|

Arch_ID |

Site_ID |

Feature Type |

Description1 |

Description2 |

Area_m2 |

|

126 |

126 |

Site |

"Mayemeja 1" |

Workshop and upper sector |

6,007.0 |

|

127 |

126 |

Structure Locus |

Walls |

Corral area |

130.6 |

|

275 |

275 |

Site |

"Mayemeja 5" |

Lower slopes parallel to bofedal |

10,401.4 |

|

276 |

275 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Eroded terraces along lower slope |

1,414.2 |

|

277 |

275 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Eroded terraces along lower slope |

978.2 |

|

278 |

275 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Eroded terraces along lower slope |

524.6 |

|

279 |

275 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Eroded terraces along lower slope |

1,234.2 |

|

280 |

275 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Eroded terraces along lower slope |

4,306.6 |

|

324 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

Medium Density |

Concentration in on top of lava outcrop |

49.6 |

|

325 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

High Density |

Flakes washing down from structures |

12.4 |

|

326 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

High Density |

Concentration in sheltered area |

4.5 |

|

327 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

Medium Density |

Expanse of flaked stone |

182.4 |

|

328 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

Low Density |

Light scatter coterminous with site bndy |

2,942.7 |

|

329 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

Medium Density |

Expanse of flaked stone |

940.5 |

|

330 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

High Density |

Workshop mound |

292.1 |

|

333 |

126 |

Lithic Locus |

Medium Density |

Concentration in sheltered area |

15.6 |

|

334 |

126 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Eroded terraces along lower slope |

1,504.4 |

|

335 |

126 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Base of circular structure |

4.3 |

|

336 |

126 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Base of circular structure |

5.2 |

|

337 |

126 |

Structure Locus |

Wall bases only |

Base of circular structure |

5.5 |

Table 6-48. Areal features belonging to A03-126 and A03-275 workshop complex.

Spatial features in this area were initially delimited with dGPS and then, during a visit in 2004, the boundaries of the smaller structural features were remapped with a total station.

Terraces and structure bases

At an altitude of nearly 5000 masl in sandy soil, this area is far above the growing zone even for tubers. If these were residential terraces, where were the ceramics? One possible explanation was provided from three14C samples from the workshop test unit [Q02-2u3] that revealed that the workshop occupation belonged to the preceramic and very early ceramic period. It appears that that the dominant component of this site is from prior to the use of ceramics in the area.

The terrace margins are generally highly eroded and ill-defined in places, and the focus in 2003 was therefore on mapping terraced zones as several large polygon areas rather than attempting to map each terrace as a linear feature. The upper terraced area [A03-334] was particularly eroded, but faint traces of intermittent terraces were apparent. The terraces walls, and wall bases that appear to have been small circular structures, are single walled with no mortar. The sole exception was a corner of doubled-walled construction made of ground fieldstone in the lower terraced area [A03-276] where the corner of a structure of cut-stone masonry of possible Late Horizon date was located, a feature that is described later in the Late Prehispanic Block 1 section.

The eroded terraces of A03-275 are generally 20-50cm in height and are constructed with fieldstones of a variety of sizes. Typically, a few large boulders will form the general structure of the terraces, and then small level surfaces would be constructed by building terrace walls of the flat local lava rock. It is difficult to date these constructions but due to the presence of sherds from several Inka plates, and a possible LH feature, these terraces are further discussed in the Late Prehispanic section titled A03-275 "Maymeja 5", along with several photos of these constructions.

In the sector of A03-126, above the bofedal margin, several small circular structures [A03-335] of possible Early Agropastoralist age were identified. These structures consist of circular wall-bases with concentrations of obsidian eroding downslope from the interior area. Two adjacent circular constructions were in the middle of an eroded terrace, but the predominant pattern was for small circular constructions measuring 2-3m in diameter to be built adjacent to rock outcrops that appear to offer protection from the western winds. These small wall-bases were observed along the expansive rock outcrop that extends just south of the bofedal. No hearths or bones were observed in this area, although bone preservation would probably be very poor in this exposed area.

Figure 6-53. Base of structure [A03-335] is formed by fifteen large, partially buried stones and measures 2.5m in diameter.

These structures are being interpreted as residential constructions or windbreaks occupied on short term basis by obsidian procurers who were allowing their animals to graze while they quarried and reduced obsidian from the Maymeja area, and perhaps dug the quarry pit Q02-2. Herders would presumably have had sufficient animal hides and woolen textiles to insulate stone walled structures from the penetrating winds.

It is also conceivable that these are bases for large circular LIP chulpas, as the wall bases are sufficiently large. This is unlikely, however, as there were no LIP ceramics in the area, and the obsidian flaking debris eroding downhill strongly suggests that obsidian reduction was occurring inside these circular structures.

Workshop mound

The workshop mound [A03-330] forms the largest and highest density of flaked obsidian observed in the Upper Colca project region. The 1x1m test excavation in this mound (Section 7.4.2) revealed episodes of reduction activity that generated cultural levels with distinctive concentrations of knapping debris associated with early stage reduction. The flake densities attenuate away from the mound center where the test unit was placed, and immediately south-west of the mound a corral is evident that is probably relatively ancient. One possibility is that animals were loaded with obsidian inside the corral subsequent to knapping at the workshop.

A03-209 "Maymeja 7"

Approximately 700m to the south-west of the workshop area another concentration of culturally derived obsidian flakes was encountered, and this concentration was distinct in that it was well-removed from the area with naturally abundant obsidian. A small cavity in a rock face was located with what appeared to be a wall in back and a large obsidian scatter extended down the hill below the wall cavity. The rock cavity may have contained a burial at some point, but the space was empty save for a few LIP sherds. This reduction zone was notably distant from the obsidian source, away from the bofedal, and was uphill and on a relatively steep slope (25º) high above any of the eroded terracing. Given the density of this reduction area, including two high density loci measuring 17m2and 39m2, the best explanation appears to be that this site conforms to the previously observed pattern of obsidian reduction occurring on the western lip of the Maymeja area where the views westward are excellent (see interpretation in Section 8.3.3 ). The mean visibility value for features in Block 1 overall is 18.5, while the visibility value for A03-209 is 31, or 40% higher than the average visibility in Block 1.

Figure 6-54. A03-126, 209, 275 Maymeja workshop and vicinity.

A03-201 "Saylluta 2"

This site consists primarily of a medium sized corral built among large colluvial boulders that have descended from the north margins of the Maymeja area. The area is littered with obsidian flakes, and natural and culturally fractured obsidian flakes cover the ground. It is perhaps due to the extensive glaciation in the area that the sandy soils of this corral contain a low density of geologically fractured obsidian flakes.

Figure 6-55. View looking south from above at A03-201 "Saylluta" with excavation of test unit Q02-2u1 under way in top center of corral by the orange bucket. Site datum is on top of the large boulder to the south of Q02-2u1 (just above test unit in the photo).

The corral offers excellent protection from the mountain winds that prevail on the southern edge of the Maymeja area, but at the cost of warmth from direct sunlight. In early August the sun would disappear from this area around 4pm. As is visible in Figure 6-55, a wall between 1.5m and 2m in height encircles this corral, and constructed stairs access the corral from the south. A fan of flaked obsidian, bone fragments, and a few unslipped, unpainted pottery fragments extends 20m downslope from the access stairs to the edge of a grassy area that has probably been a bofedal during wetter times.

A test unit [Q02-2u1] was placed on the southern half of this corral, and it revealed a fill of sandy local soil, and perhaps camelid dung, that was used to level out this corral in an otherwise sloping area. A discouraging colonial-style nail was encountered in level 4 of this test unit, suggesting a post-conquest occupation, nevertheless the test unit was excavated to sterile where large, irregular rocks cover the base of the 1x1. No distinctive prehispanic features were identified, and as yet the small pieces of carbon recovered from this test unit have not been analyzed with14C dating.

This corral is a suitable shelter from wind and it is also relatively well hidden and could serve as a refuge as it goes unnoticed among the talus boulders of northern Maymeja. Due to the lack of sunlight during the winter months, and the relative scarcity of water adjacent to A03-201 under current conditions, this location is thermally a less comfortable camp as compared with the sites on the southern edge of Maymeja.

A03-570 "Valdivia 1"

At the lower end of Maymeja, close to where the principal trail arrives in the zone from Chivay, a large obsidian scatter was encountered adjacent to an active estancia owned by Eliseo Vilcahuaman Panibra but occupied by Timoteo Valdivia who was hired to guard the herd. The site of A03-570, defined by a low density scatter of obsidian flakes, occupied the entire east slope of a large breccia promontory that forms one of the distinctive landmarks on the western edge of Maymeja. A relatively large (419m2), medium density scatter [A03-572] is located on the northern end of this area, where the water from the northern half of Maymeja cascades over the breccia layer and descends steeply into Quebrada de los Molinos.

The site of "Valdivia 1" [A03-570] appears to be a prime site for occupation by pastoralists. The excellent views of two of the largest bofedales in the Maymeja area, extensive sun throughout the day, and a position on the lee side of a promontory protecting it from the westerly winds make this place a desirable location for pastoralists in the area. This site, and the adjacent site of A03-190 at the head of the trail from Chivay, belong to a cluster of sites that occupy the steep western margin of the Maymeja area and that provide sweeping views of the Quebrada de los Molinos. This site has a high visibility index, particularly from the lithic locus A03-571, where a visibility index value of 40.6 was calculated that can be compared with a mean visibility index of 18.5 for sites in Block 1. An interpretation of these viewshed values is discussed in Section 8.3.3.

A03-539 "Mamacocha 5" and A03-548 - "Mamacocha 6"

These pastoral bases in the upper end of Quebrada de los Molinos have been considered bases because of the remnants of large corrals found in therein. However, these sites lack temporally diagnostic materials. This area consists of moraines with large lava boulders that have descended from the steep slopes above and offer wind protection as well as a few small rock shelter features.

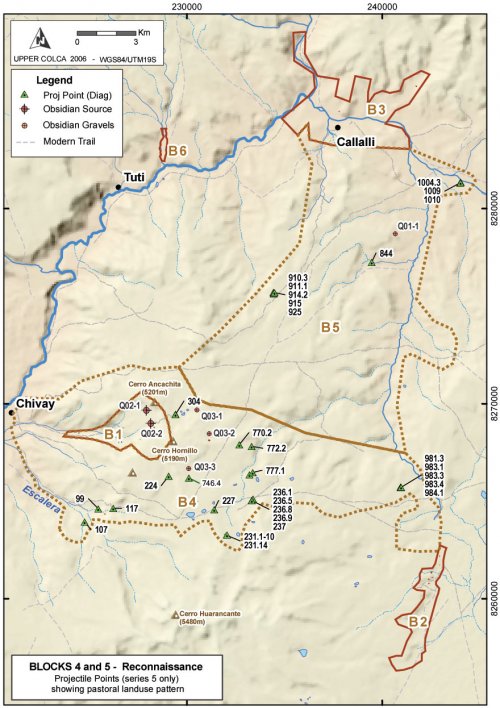

Blocks 4 and 5 Reconnaissance Areas

The diffused nature of pastoral settlement was evident from the distribution of land use observed in the extensive Blocks 4 and 5 zones. These areas primarily consist of rugged lava terrain that appear desolate in the dry season. In the wet season, however, there are probably adequate grazing opportunities through these areas. By distributing pastoral impacts over the larger landscape during the wet season, the bofedales would be allowed to recover.

Figure 6-56. Blocks 4 and 5 showing Series 5 projectile point distribution.

Series 5 projectile points are not exclusive to the Early Agropastoral period, but given the increase in obsidian production during that period, this dataset provides a perspective on this period that is not available for this transitional stage between diagnostic lithic and ceramic technologies. One informative aspect of the Blocks 4 and 5 projectile point distributions is from the types of obsidian in use for projectile point manufacture. Recall that much of the obsidian surface gravels available at around 4975 masl on the eastern flakes of Cerro Hornillo contain deficiencies either because they contain heterogeneities or because they derive from smaller nodules. Projectile points from Blocks 4 and 5 are almost never made from material with heterogeneities.

|

Proj Points |

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Total |

|

5 |

25 |

1 |

1 |

27 |

|

5a |

2 |

2 |

||

|

5b |

2 |

2 |

||

|

5d |

9 |

9 |

||

|

Total |

38 |

1 |

1 |

40 |

Table 6-49. Material types for Series 5 points in Blocks 4 and 5.

This table demonstrates that despite the proximity of many of these sites to Ob2 surface obsidian gravels with heterogeneities, the Ob2 material was almost never used for point production. The obsidian observed on the eastern flanks of Hornillo did not entirely consist of Ob2 material with heterogeneities. In fact, the Q03-3 source south of Hornillo contained nodules measuring 15 cm across free visible heterogeneities. The Q03-3 material, however, did not appear as transparent as the Q02-2 glass from Maymeja.

Discussion

During the Early Agropastoralist period in the obsidian source area observed what appears to be intensive obsidian production in the initial stages of reduction at a workshop 600m downslope from the quarry pit, as well as evidence that suggests that obsidian was being transported away from the Maymeja area as whole nodules.

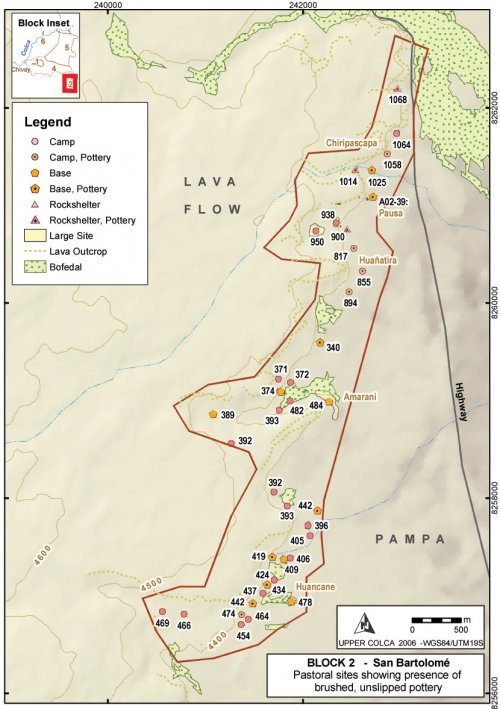

6.4.2. Block 2 - San Bartolomé

As with the obsidian source area, the economic pattern from the San Bartolomé area is predominantly pastoralist, making it difficult to isolate sites belonging to the Early Agropastoral period from Late Prehispanic and colonial period camelid pastoralist sites. The unslipped, unpainted pottery with a brushed interior resembling the Chiquero type is found in this area, but the pastoral camps are mostly multicomponent such that sherd concentrations on the surface are largely mixed with painted styles, colonial styles and utilitarian modern pottery. The majority of these pastoral sites contain obsidian flakes and virtually all the obsidian is the Ob1 obsidian that derives from the Maymeja area of the source.

It should be noted that hunting opportunities abound in this area, and textured landscape atop the lava flow area of Block 2 is popular with hunters to this day. Herders during the Early Agropastoral period probably supplemented the returns from the herds by hunting viscacha, tarucadeer, and perhaps wild camelids.

Figure 6-57. Block 2 - Early Agropastoral occupation.

Evidence from ceramics

While single-component sites are rare in Block 2, most sites conform to a distributed pastoralist settlement pattern, spatial patterning is evident in the distribution of a brushed, unslipped type of pottery in neckless olla forms in Block 2. This pottery type bears resemblance to the Chiquero type proposed for the Formative Period in the main Colca valley by Wernke(2003). However, as will be discussed further, test excavations found pottery with similar characteristics in contexts dated to the 1313±36 B.P. (AA56939; A.D. 650 - 780) in the Block 3 area, suggesting that this pottery style continued to be used in the highland areas. Nevertheless, as shown inFigure 6-57, pastoral sites with wiped and unslipped olla sherds were found in two relatively discrete clusters in the Block 2 survey area. These sherds were found in a large cluster on the north end of the survey, and then none from A03-340 south to A03-442, and a small cluster is found in the southern most group of sites in Block 2. In other words, in the center of the survey was a zone where these pots were not encountered. The spatial patterns associated with the presence of unslipped, unpainted ceramics should not be over-interpreted because undecorated ceramics were not an artifact type that was rigorously sampled in this survey work. Furthermore, a number of small, a-ceramic sites were encountered that had pastoral attributes, such as small corral areas and relatively good access to water, yet no ceramics of any kind were evident. It is difficult to establish the antiquity of such sites, but it is possible they date to earlier stages of the agropastoral economy when ceramics use was .

It is worth noting that there was a strong association observed between high-density lithic loci predominant in obsidian raw material, and sites with this wiped, unslipped pottery type. Of the 22 high density lithic loci, 19 of them (86%) fell in sites that also had the unslipped, possible Formative (Chiquero) pottery in question. Among medium density scatters the pattern was less dominant. Of the 23 medium density lithic loci, 14 (60%) were found in sites with the unslipped pottery. While sites and surface artifacts are highly commingled in this area, these patterns suggest that obsidian production was associated with the pastoralists who made use of the wiped, unslipped olla design. Due to the limited sampling of unslipped ceramics, the associations between this pottery type and obsidian reduction are not certain.

Pastoral site classifications

The evidence of extensive pastoral production along the margins of the pampa in Block 2 consist primarily of the structure bases from pastoral features along the margins of grazing area, primarily corrals, and associated artifact scatters. These pastoral facilities can be subdivided in terms of the size of the corral features and the apparent length of occupation based on artifact densities. Environmental characteristics do not help with isolating pastoral site groups, perhaps because the priority placed upon access to pasture dominates the site placement criteria. The mean slope of pastoral sites of various groupings in Block 2 is between 7-8°, and the most well-represented aspect for sites was the eastern aspect, accounting for 40 Block 2 sites.

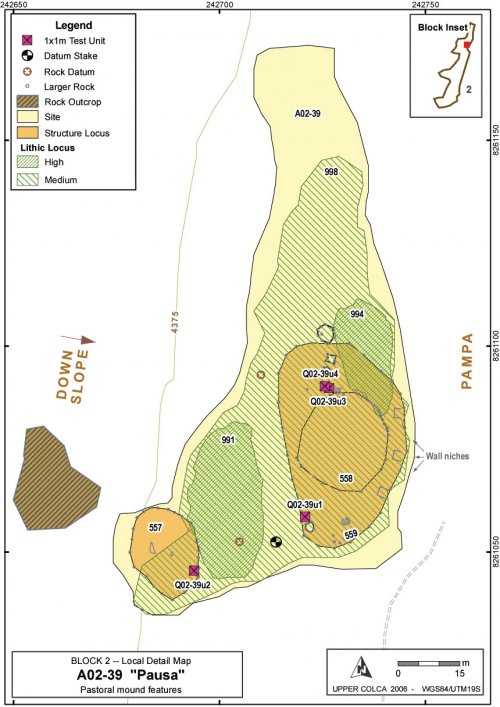

A02-39 "Pausa 1"

The site of Pausa 1 was initially visited in 2002 following consultation with Dr. José Antonio Chávez (2001, Pers. Comm.) who explained that this entire area had been visited, and partially collected, by his student groups in the 1980s. Despite the earlier collection programs by Arequipa students, the 2003 survey team was able to locate large quantities of projectile points and some ceramics of both local and non-local stylistic groups. As described above, the raised corral structures are found along the edge of a large pampa paralleling the base of a lava flow from Huarancante. The broadest of these corral structures, and the group with the most interesting wall-base constructions, were the oval structures of Pausa. With a permit from the INC to place up to four 1x1m test units in this site the 2003 field team spent a number of weeks testing this site as reported in [Section 7.5] These test units revealed an occupation spanning the Late Formative Period, but ceramics and mortuary structures from later periods were also encountered here.

Figure 6-58. Pausa [A02-39] showing raised oval structures, lithic concentrations, large rock forming wall bases, and test unit locations. Site mapped with Topcon total station and dGPS.

|

ArchID |

Description |

Number of |

Dimension (m) |

Size (m2) |

|

A03-557 |

Raised surface on slope to southwest of main Pausa site encircled by large rocks. Fill on downslope edge leveled the internal area. |

26 |

15 x 20m, circular |

271.8 |

|

A03-558 |

Area in center of Pausa site encircled by large rocks. |

28 |

20 x 25m, circular |

441.7 |

|

A03-559 |

Oval area raised ~1m off of the pampa and encircled with large rocks including a distinctive wall construction on east side with three niches in wall. |

27 |

30 x 50m, oval |

1175 |

Table 6-50. Dimension of structural features at Pausa [A02-39].

The structures at the Early Agropastoralist base of Pausa include two large, raised corral areas that are most evident because large rocks form a circle that appear to be wall bases from old corral walls. The largest of these rings is oval [A03-559] and it contains a smaller, circular structure [A03-558]. The larger rocks that encircle these features and form the wall bases are between 50cm and 100cm across, and the rocks are partially buried. Interestingly, the ovals all have approximately the same number of these large rocks (between 26 and 28), such that encircling the larger ovals the spacing between the rocks is larger than it is around the smaller ovals. As is evident in Figure 6-58, the rock spacing around A03-559 is approximately 5-7m, the spacing in A03-558 is highly irregular, and the spacing between rocks in the A03-557 oval is approximately 2-3m between rocks. The rocks could have represented the foundation rocks for corrals, but these would have been very substantial corrals and far larger than any contemporary corrals that were encountered in the region.

Figure 6-59. Circular structure A03-557 extends from 1m behind the tape to just below the largest rocks at the back of the photo.

Figure 6-60. Testing u3 and u4 on north edge of structures A03-558 and A03-559. This photo is taken from above, from the base of the lava flow.

Lithics

The site of Pausa was somewhat atypical of Block 2 raised corral features due to the size and diversity of materials found there. The material types in use indicate that, while a variety of material types were available, obsidian was more intensively processed in this area than other material types.

|

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Chert |

Total |

|

|

Cores |

1 |

1 |

2 |

||

|

Flakes |

52 |

7 |

5 |

10 |

74 |

|

Points & Tools |

8 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

|

|

Total |

61 |

9 |

5 |

11 |

86 |

Table 6-51. Counts of lithics from surface collection at Pausa [A02-39].

Table 6-51 can be compared with the surface collection at Taukamayo in Block 3 (Table 6-54) where surface materials point to a greater availability of chert and quartzite in Block 3. While Pausa is somewhat deflated and eroded in places, it did not have a landslide like the site of Taukamayo exposing quantities of obsidian.

Discussion of Pausa

Pausa appears to have been one of the larger and more varied sites in the Block 3 settlement area, yet, based on surface artifacts, the activities at Pausa were fairly typical for these raised corral features. These include a variety of lithic reduction but, above all, a dominant presence of Ob1 obsidian. This relatively consistent access to Ob1 obsidian suggests that the Early Agropastoralists of Block 2 were affiliated with, or directly responsible for, some of the quarrying and production activities that were observed in the Block 1 Maymeja area.

The size of these structures, the regular spacing of large rocks, and the presence of regular rock "wall niches" on the eastern edge of A03-559 suggest that these platforms served as more than mere corrals and there this was also a locus for ritual activity. Obsidian was widely used in the Block 2 area on the whole, but the quantities at Pausa appear to have been far greater than at neighboring sites. It is possible that this site served as some kind of aggregation spot in the Block 2 puna, although it is difficult to speculate without further examination of this site. Test excavations revealed primarily a small hearth in a very small circular structure (Section 7.5.2), and evidently further excavation work is needed at Pausa.

Discussion of Block 2 Early Agropastoralists

Depending on the degree of re-occupancy in prehistory, the principal pastoral base sites with their associated corrals that were recorded are larger than one would expect given modern pastoralist behavior in the area. The herd sizes that noted in the Block 2 area during fieldwork between August and December 2003 were not carefully studied, but the herds seemed sufficiently large to use a corral 50m long corral as was noted at Pausa. However, herds would not require many corrals like Pausa in one area unless the herd sizes were significantly larger, perhaps growing and shrinking with the seasons. There are corrals of comparable size in the region, but the uncertainty lies in judging how many of these corrals were in use simultaneously.

It is possible that these corrals were used by passing caravans. As a perimeter settlement represented largely by groups linked to Colca Valley communities (as indicated by ceramics styles), it is possible that these larger facilities were designed to host passing caravans.

Pastoral Camps and rock shelters

The two smaller collections of Early Agropastoral sites in the Block 2 are grouped as "Pastoral Camps" and "Rock shelters". These sites consist of small enclosures and limited surface expression of ceramics from the Formative Period. The rock shelters often have geometrical, abstract parietal art on natural walls drawn in ochre. Often these sites will also have colonial rock art, typically Christian themes (such as the cross, or a Virgin Mary) in ochre as well, but these were excluded here from this review of prehispanic sites. The smaller sites could have been day-use areas as part of a strategy to distribute the impact of grazing. The rock shelters were generally small and may have been day shelters from weather as well as night shelters for very small groups.

Pastoral Bases

These are the largest sites in Block 2. They consist of pastoral facilities, associated residential structures and adjacent middens, and an artifact scatter extending along the margins of the grazing area. These sites are commonly found on a sloping area or a raised area along the margins of the pampa where the drainage is adequate. Animal control structures were frequent on these sites, with the majority of them taking the form of maintained or abandoned corrals of varying sizes. At the sites designated as "Pastoral Bases", corral structures were mapped and they range in area from 62 m2to 4,306 m2with a mean corral size of 671m2. Due to high rates of erosion, it was difficult to confirm from the soil consistency if it was largely dung soil inside of structures that appeared to be long-abandoned corrals. However, the raised area of these corrals are effectively low mounds that may be the result of accumulation of dung over long time periods, combined with some building up and filling in of the raised area to lift the corral areas off of the level of the pampa to improve drainage and avoid inundation during the wet season.

Structures

These structures on the puna edge appear to be pastoral facilities containing the bases of walls formed by rocks between 30 cm and 100cm in size that create a circular or elliptical enclosure. The area will often contain smaller enclosures that probably served more specifically as corrals, subdividing the protected area. These corrals might be occupied simultaneously or sequentially, and could contain individual herder's animals, or they may segregate the herd into sex and age categories as a part of pastoral management strategies (Flannery, et al. 1989;Flores Ochoa 1968). The presence of such large rocks at the base of these walls is perhaps explained by the need to keep small animals, such as young camelids, inside and the need to keep small predators out. Modern herder-built walls are often solidly constructed along the base and only along the top of the wall do smaller rocks get used.

These wall bases could be the remnants of corrals used by seasonal residents of this rich pasture region, or if they were used by passing caravans, the corrals could have been important facilities as part of a multi-day rest stop for caravans (Lecoq 1988: 185-186;Nielsen 2000: 461-462, 500-504;West 1981: 70).

Artifact scatters

The perimeters of pastoral bases often have dense artifact scatters, including pottery fragments from a variety of time periods, however there was a relatively low frequency of high density lithic loci inside of pastoral bases. When all of the high density loci are considered, only 30 (23%) of the high density lithic loci were located in sites classified as "pastoral bases".

High density lithic loci in this region primarily consist of obsidian flakes and it appears that, despite being located off of the pastoral base sites, these high lithic concentrations still seem to be associated with early pastoral occupations. This inference is based on two aspects of these high density loci: (1) most of the pre-Series 5 projectile points are not obsidian, while most of the Series 5 points are obsidian, and therefore if point production was occurring they were probably making Series 5 points; (2) if merely flakes were being produced, such production was probably linked to pastoral butchering, and therefore the obsidian is again linked to the pastoral occupation of the area. Why, then, were the high concentrations located outside of the pastoral base areas as noted above? One possibility is that one may be seeing a site maintenance pattern where some lithic production is occurring offsite during pastoral herding so that the residential base is not littered with sharp flakes.

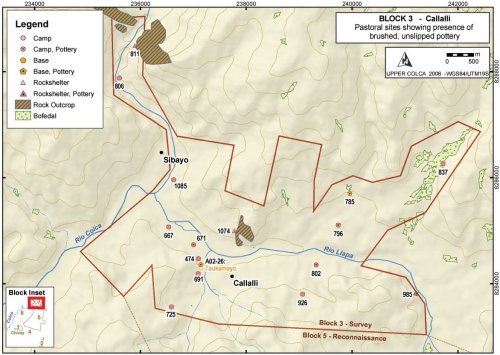

6.4.3. Block 3 - Callalli

An Early Agropastoral period occupation of the Block 3 area is evident from survey work, but it is less dense than was encountered for this time period in Block 2, and it is also more faint than the evidence from the Late Prehispanic in this the Block 3 area itself.

Figure 6-61. Early Agropastoralist settlement in Block 3.

The Early Agropastoral settlement in the Callalli area is difficult to isolate from later pastoral settlement, but the evidence that was encountered suggests that it was a distributed settlement pattern with similarities to the pastoral pattern observed elsewhere in the higher altitude portion study area. The criteria used to discern this settlement pattern were sites with pastoral attributes (grazing lands, water), and the potentially the presence of the unslipped Chiquero type ceramics considered Formative in the main Colca valley by Wernke (2003).

Occupations are generally small and diffuse, with rock shelters and river terraces providing the majority of the settlement locations. The rock shelter of Quelkata [Q03-985], described in the preceding Archaic Foragers - Block 3 section, had a substantial a-ceramic occupation. However the vast majority of the projectile points analyzed by Chavez (1978) appear to fall into Series 5 in the Klink and Aldenderfer (2005) typology, placing the occupation in the Terminal Archaic. Elsewhere in Block 3, several multicomponent sites were occupied during this time period, most notably Taukamayo [A02-26].

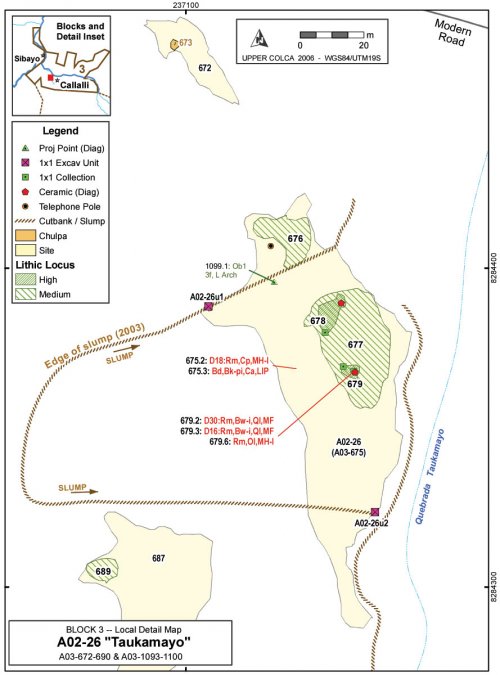

A02-26 "Taukamayo"

The multicomponent site of Taukamayo sits on a terrace above Quebrada Taukamayo just west of the modern town of Callalli. In the course of the 2003 survey the site was surface mapped as A03-675 in keeping with the 2003 survey methodology, but the official site number on the test excavation permit is A02-26. The site was tested with a 1x1m test unit and two partial units that produced dates circa cal AD650 (Section 7.6.1).

The site is located on a terrace above a tributary to the Río Llapa immediately upstream of the large confluence with the Río Colca. Located in a parcel owned by Noemi Ramos, who resides primarily in Arequipa, the site is located across Taukamayo creek from the modern village of Callalli. The town site of Callalli has Inka and possibly earlier components evident on the western edge of the town limits, but the occupation encountered at Taukamayo is earlier.

It is possible that Taukamayo was a peripheral site to the principal settlement at Callalli. Nielsen's (2000: 465-468, 490) ethnoarchaeological research on camelid caravans notes that when caravans stop overnight at settlements they will frequently camp in areas segregated from the principal settlement for two reasons. First, interference in the activities of residents, stampedes, and other forms of conflict can be avoided by remaining on the periphery of the settlement. Second, the agricultural fields can be better defended from caravan animals by camping a prudent distance from farm plots. In the modern trail system the principal route linking the Callalli area with the Chivay obsidian source and other high puna regions to the south climbs the Taukamayo drainage. Thus, Taukamayo may have represented a kind node in a larger transportation network because it is a relatively large site lying precisely in the area where the highland trail system joins the river network, but it is across the drainage from the settlement of Callalli.

Figure 6-62. Taukamayo [A02-26], a multicomponent site partially destroyed by a landslide.

Figure 6-63. Overview of Taukamayo [A02-26] on slump along base of hillside. Grey box shows area detailed in Figure 6-64, below.

Figure 6-64. Taukamayo [A02-26] detail showing two test units locations on cutbank margins of the creep area. Excavators are visible on right-side at A02-26u1 and provide scale for photo.

Ceramics

The multicomponent nature of this site is most evident from the spatial and temporal variety of pottery styles observed here. This site contained the only pottery diagnostic to the Titicaca Basin Formative, and it also has a sherd from a Titicaca Basin LIP beaker. Tiwanaku sherds, however, are conspicuously absent as they are elsewhere in the valley contrasting with regional obsidian distributions.

|

Period |

Estilo |

Beaker |

Bowl |

Olla |

Neckless Olla |

Plate |

Cup |

Unknown |

Total |

|

LH |

Collagua-Inka |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|||||

|

LIP-LH |

Collagua |

1 |

1 |

||||||

|

LIP |

Colla |

1 |

1 |

||||||

|

MH |

Local MH |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|||||

|

F-MH |

Chiquero-like |

2 |

1 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

8 |

25 |

|

|

MF |

Qaluyu-like |

2 |

2 |

||||||

|

Total |

6 |

3 |

7 |

7 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

34 |

Table 6-5. All ceramics from Taukamayo [A02-26] and vicinity.

Evidence from ceramics reveal that while the site has components from all ceramics-using periods, the strongest evidence is from the earlier periods, particularly from the unslipped, brushed ware that has similarities to Chiquero style from the main Colca valley. These Chiquero-like sherds at Taukamayo are notable because this style of sherd is abundant at this site, and while this style was widespread in Block 2 the 2003 survey data shows that Taukamayo is the only location in Block 3 where Chiquero style sherds were encountered.

Surface collection in the slump debris at the site also revealed several sherds that appear to belong to Titicaca Basin styles, representing one of the few pieces of possible evidence of reciprocation for the quantities of Chivay obsidian that have been found in the Titicaca Basin. These Titicaca Basin styles include two sherds with similarities to the Middle Formative north Titicaca Basin style Qaluyu or early Pukara.

Figure 6-65. Non-local incised and stamped pottery from Taukamayo [A02-26], in the 2003 provenience these are A03-679.2 and A03-679.3.

Furthermore, a Colla sherd from the Titicaca Basin LIP was found here. The relatively high density of non-local ceramics from Taukamayo supports the idea that Taukamayo was a camp for non-local passersby, and perhaps caravan moving through the upper Colca valley.

Condition of Site

The site was partially destroyed by a broad slumping of the hillside above the site. Callalli residents (Ramos, Ordóñez, Windischhofer) have indicated that the creeping displacement began during the rainy season in early 2001.. Down-cutting in the stream bed of the adjacent Quebrada Taukamayo may have contributed to the recent creep. A historically large El Niño - Southern Oscillation occurred in the years 1997-1998, and a smaller one occurred in 2002-2003, therefore the slumping was not immediately attributable to the unusually heavy ENSO rainfall. Furthermore, a 2.5 m deep trench diverting water from the slope above Callalli was cut in the recent past, and this trench diverts water into the Quebrada Taukamayo watershed. The increased water volume in the quebrada beginning after the 1997-1998 ENSO and with additional water from the Callalli diversion trench, is perhaps contributing to a significant down-cutting of the stream bed which leads to a greater overall gradient of the slope and greater probability of sliding.

In the debris pile at the base of this landslide, ceramics from a variety of time periods were encountered, revealing the multicomponent nature of the settlement. While the landslide has destroyed much of the site, and threatens to destroy more area immediately north and south of the current slide zone, the creep has presented a few opportunities for archaeological observation as well. First, in the debris pile at the base of the slump one is able to observe ceramics from throughout the temporal sequence at the site. Second, in the cut on the north and south edges of the landslide, places where the cut varies between 50cm and 200cm in height, the 2003 survey team was able to observe lenses containing ash, bone, lithics, and pottery, permitting a relatively targeted testing of this deposit.

Discussion

It is immediately apparent that Taukamayo is an unusual site in the Block 3 area. The variety of ceramics and the diversity of lithic material types suggest that the occupants of the site participated in the circulation of goods on a larger geographical scale than did other sites in the region. Furthermore, while bifacially flaked obsidian implements were not uncommon in Block 3, these artifacts appeared to be relatively highly curated. At Taukamayo, reduction evidence from unmodified flakes and cores of obsidian was widespread.

The diversity of ceramic types observed at this site, and the potential for encountering ceramics from various stratigraphic levels in the mixed debris of the slump deposit, was significant. Non-local materials were encountered in styles belonging to the Titicaca Basin dating to the Middle Formative and the Late Intermediate Period, however in the broad sample provided by the Taukamayo landslide debris there was a notable lack of diagnostic ceramics from the time periods featuring the most political integration in the Titicaca Basin: the Late Formative polities and the Tiwanaku period.

Lithics

The most notable feature of Taukamayo was the relatively high density of obsidian as compared with other areas of Block 3. It appears that obsidian reduction occurred here on a number of occasions and due to the landslide, obsidian flakes appear in many parts of the slide deposition pile.

|

Taukamayo Cores - Surface |

Entire Block 3 Surface Collection |

|||||||

|

Material |

No. |

m Cortex |

mWt |

sWt |

No. |

m Cortex |

mWt |

sWt |

|

Obsidian |

10 |

25 |

14.31 |

7.8 |

17 |

5.0 |

23.2 |

13.1 |

|

Volcanics |

- |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

7.5 |

87.7 |

42.6 |

|

Chalcedony |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4 |

16.7 |

47.5 |

18.1 |

|

Chert |

1 |

0 |

34.4 |

- |

18 |

32.1 |

57.17 |

33.8 |

|

Total |

12 |

32.1 |

48.4 |

29.0 |

41 |

21.6 |

43.6 |

31.3 |

Table 6-53. Cores from the surface of Taukamayo as compared with the entire Block 3 surface collection.

Obsidian cores (all Ob1) were relatively abundant at Taukamayo but they were not exceptionally common. Nodules of black and tan colored chert were observed in the creek bed at Taukamayo and the material was being flaked elsewhere on terraces adjacent to the creek, but curiously only one core of this chert was found at Taukamayo. The distribution of obsidian material at the site suggests that a range of reduction stages on obsidian were occurring in this location and comparably less of the local chert or quartzite material was in use.

|

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

Quartzite |

Total |

|

|

Flakes |

138 |

199 |

53 |

25 |

181 |

79 |

675 |

|

Cores |

11 |

8 |

- |

2 |

4 |

1 |

26 |

|

Points & Tools |

22 |

15 |

1 |

- |

1 |

- |

40 |

|

Hoes |

- |

- |

16 |

- |

- |

- |

16 |

|

Total |

171 |

222 |

70 |

27 |

186 |

80 |

757 |

Table 6-54. Counts of lithics from surface collection at Taukamayo [A02-26].

This table shows that counts of obsidian are relatively high at Taukamayo. These counts should not be compared directly with other sites in Block 3 because these analysis results reflect two unusual aspects of Taukamayo. First, the high counts at this site are, in part, due the visibility of lithics in the debris from the landslide. Second, a detailed lithics analysis was conducted on the excavated materials from A02-26u1, as well as on surface materials from this site, and these high counts reflect this detailed analysis.

Chert and quartzite are immediately available in this area, and yet these material types are the minority in representation in flaked stone artifacts at the site. Secondly, Ob2 obsidian was relatively common at Taukamayo. As compared with the Block 2 site of Pausa (see Table 6-51 in Block 2 discussion) where obsidian use is primarily (87%) Ob1 material, at Block 3 Taukamayo there appears to be less concern for the clarity of the material or the presence of heterogeneities because 57% of the obsidian artifacts are Ob2 material. In fact, Taukamayo contains the highest proportion of bifacially flaked tools made from Ob2 material from the entire survey area. Notably, however, these were primarily bifaces not points, as only two of the artifacts made from Ob2 obsidian were projectile points.

Figure 6-66. Sixteen large andesite hoes were found at Taukamayo [A02-26].

Finally, this site contained an exceptional collection of sixteen large, broken andesite hoes. The hoes varied considerably in size, and it is difficult to assess the original, unbroken size of the items. The hoes ranged in weight from 112g to one as large as 1189g (shown in Figure 6-66, right), with a high variance. All showed signs of intial shaping with percussion flaking as well as flake scars from use. The mean weight was 512g, but with a standard deviation of 483.7.

These hoes had bifacial flaking on the working edge, and most showed polish from use, but no hafting wear was observed under visual inspection. The source of the andesite has not been determined, but if the source lies somewhere distant it is possible that, as with obsidian, Taukamayo contained a high percentage of non-local lithic materials that contrasts with neighboring sites in the area (see lithic analysis data reported in Section 7.6.1).