6.2.1. Material type by survey block

Lithic raw material in the vicinity of the Chivay source

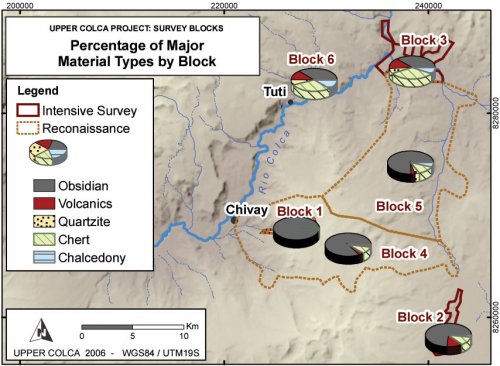

Variability in material type throughout the survey area make clear the basic structure of lithic procurement in the area of the Chivay source.

Figure 6-1. Artifactual lithic material types in theUpper Colca Project study region.

|

Obsidian |

Volcanics |

Chalcedony |

Chert |

Quartzite |

Total No. |

||||||

|

Block |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

|

1 |

381 |

97.9 |

2 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

6 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

389 |

||

|

2 |

369 |

72.9 |

71 |

14.0 |

11 |

2.2 |

50 |

9.9 |

5 |

1.0 |

506 |

|

3 |

149 |

39.3 |

45 |

11.9 |

26 |

6.9 |

139 |

36.7 |

20 |

5.3 |

379 |

|

4 |

190 |

85.2 |

9 |

4.0 |

6 |

2.7 |

18 |

8.1 |

0.0 |

223 |

|

|

5 |

235 |

75.6 |

13 |

4.2 |

15 |

4.8 |

36 |

11.6 |

12 |

3.9 |

311 |

|

6 |

22 |

39.3 |

6 |

10.7 |

6 |

10.7 |

19 |

33.9 |

3 |

5.4 |

56. |

|

Total |

1346 |

72.2 |

146 |

7.8 |

64 |

3.4 |

268 |

14.4 |

40 |

2.1 |

1864 |

Table 6-5. Counts of artifactual lithics material types throughout the study region.

The availability of raw material throughout the region is inferred from the variability by material type from artifact collections throughout the study region. In the volcanic region of Block 1 and Block 4, obsidian is the principal locally available material. Block 4 extends into lower elevations regions on the east and west, and chert may be available in streambeds in those regions. Block 2 has larger quantities of fine-grained volcanic stone, mostly andesites, and these were heavily used in Late Archaic. Chert is relatively abundant in Block 2 as well, which suggests that there is a chert source not far from that block. Blocks 3 and 6 show the abundance of chert and chalcedony available in the upper Colca valley area, and multicolor chert cobbles were observed in several stream beds in Block 3. Quartzite is also used in Block 3, a material that was observed eroding out of the ridgetops. Block 5, as with Block 4, appears to contain a variety of raw material types within its boundaries.

Nodules of obsidian had their geological origin entirely in the Maymeja area of Block 1 and the adjacent areas of Block 4. The only other exposure of Chivay type obsidian encountered in the course of this research was the Pulpera / Condorquiña flow - a small exposure of Ob2 obsidian nodules, all measuring less than 5cm, at the toe of a long Barroso lava flow near Pulpera in Block 5. The Condorquiña flow probably saw very little use in prehistory due to small size and poor obsidian quality.

Based on the assumption that the survey was comprehensive and that there are no other exposures of Chivay type obsidian in the Ancachita - Hornillo area, it is proposed that culturally-modified of obsidian was transported radially from the source area in Block 1 and Block 4.

Why quarry for obsidian when it can be found on the surface?

A quarry pit was located on the south side of Block 1 in the Maymeja area of the Chivay source. This quarry will be described below, as well as in Chapter 7 where the quarry pit is examined and the results are presented from a test unit placed in the debris pile associated with the pit.

(1) Larger nodules could be acquired through quarrying.

Energy was evidently expended in digging to extract obsidian at the quarry pit in Maymeja and the motivation behind this effort an important question. Looking at the general patterns over the entire study area is instructive because it reveals some general patterns that were counter to expectations of this research project. If the original nodules from the Block 1 area were of a larger size it may account for the quarrying activity observed in Maymeja.

|

Points and Tools |

Cores |

Simple Flakes |

Total |

|||||||

|

Block |

No. |

mLn |

sLn |

No. |

mLn |

sLn |

No. |

mLn |

sLn |

|

|

1 |

4 |

38.2 |

10.0 |

110 |

48.5 |

8.7 |

88 |

38.7 |

14.9 |

202.0 |

|

2 |

3 |

27.0 |

4.7 |

8 |

38.9 |

7.7 |

26 |

23.8 |

10.9 |

37.0 |

|

3 |

3 |

27.8 |

2.4 |

9 |

41.9 |

8.0 |

14 |

26.3 |

11.1 |

26.0 |

|

4 |

- |

- |

- |

33 |

41.6 |

7.5 |

34 |

34.9 |

12.2 |

67.0 |

|

5 |

1 |

28.0 |

- |

11 |

36.9 |

11.8 |

82 |

22.0 |

9.9 |

94.0 |

|

Total |

11 |

31.8 |

8.2 |

171 |

45.8 |

9.5 |

244 |

30.2 |

14.5 |

426.0 |

Table 6-6. Lengths of complete obsidian artifacts with > 30% cortex by survey block surface collections, showing means and standard deviations.

In Table 6-6 the length of cortical obsidian artifacts from surface collections from throughout the study region with a minimum threshold of 30% cortex are shown. It should be noted that tools and flakes must have 30% covering of dorsalcortex to qualify for this table, whereas cores need only have 30% cortex anywhere on the exterior surface to be included here.

The first indicator of differential activity in Block 1 is the sheer number of cortical cores in these surface collection data. Table 6-6 reveals that the mean size of cortical artifacts in all three technical classes is notably longer in Block 1, and that the second largest mean lengths are from Block 4, adjacent to the Maymeja area. The artifacts from Block 2 are surprisingly small considering that the Chivay source is only one day's travel from this location. The fact these cortical artifacts are small suggests that they did not have access to large starting nodules. Table 6-6 also shows that the cortical artifacts from Block 3 were slightly larger than one would expect considering that Blocks 5 and 2 are equidistant, if not closer, to the Maymeja area of the obsidian source than is Block 3.

(2) Obsidian from the quarry pit had more transparent coloration.

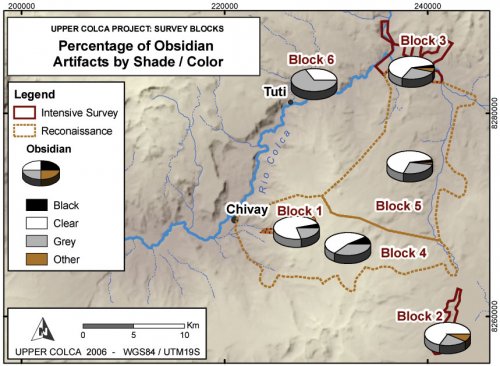

In the course of this research it was observed that there is variability in the transparency and color of culturally-modified obsidian throughout the study area and the spatial distribution is related to the appearance of natural obsidian in geological contexts. Chivay obsidian is renowned for its clarity and it is possible that material from one survey block had a greater frequency of transparency than did material from surrounding survey blocks. If clarity was a desirable characteristic of obsidian artifacts then the evidence may show a greater focus on production in areas where transparent obsidian was common. Much of the obsidian contained dark banding as well, and this banding was more visible with clear obsidian than when the obsidian matrix was a darker coloration.

Figure 6-2. Proportion of obsidian for four colors (shades) of glass, by count.

|

Black |

Clear |

Grey |

Other |

|||||

|

Block |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

1 |

13 |

4.0 |

245 |

74.9 |

66 |

20.2 |

3.0 |

0.9 |

|

2 |

1 |

0.6 |

111 |

66.9 |

40 |

24.1 |

14.0 |

8.4 |

|

3 |

3 |

2.7 |

71 |

63.4 |

33 |

29.5 |

5.0 |

4.5 |

|

4 |

12 |

8.2 |

79 |

54.1 |

55 |

37.7 |

0.0 |

|

|

5 |

5 |

2.4 |

141 |

66.5 |

61 |

28.8 |

5.0 |

2.4 |

|

6 |

0.0 |

7 |

33.3 |

14 |

66.7 |

0.0 |

||

|

Total |

34 |

3.5 |

654 |

66.5 |

269 |

27.3 |

27.0 |

2.7 |

Table 6-7. Obsidian artifact color (shade) by survey block surface collections. Includes obsidian with bands and without bands.

As shown in Table 6-7, Block 1 indeed has a higher fraction of clear obsidian than other blocks in the survey. The high incidence of clear obsidian at Block 2 (67%) further suggests that whoever was quarrying and reducing obsidian at the A03-126 workshop in Block 1 was also associated with the settlements in Block 2, as there is no naturally occurring obsidian in Block 2. As Block 2 is on the direct transport route towards the Lake Titicaca Basin, this evidence suggests that some of the clear obsidian from Block 1 was being consumed in Block 2 en route to the larger consumption zone of the south-central Andean highland region and the Titicaca Basin where Chivay obsidian was purportedly prized for its clarity. It should be cautioned that the distinction between grey and clear obsidian appears to be correlated with thickness. That is, a "clear" artifact is more likely to be considered "grey" if it is thicker because it appears to be less transparent as a result of thickness.

(3) Block 1 had more homogeneous Ob1-type obsidian.

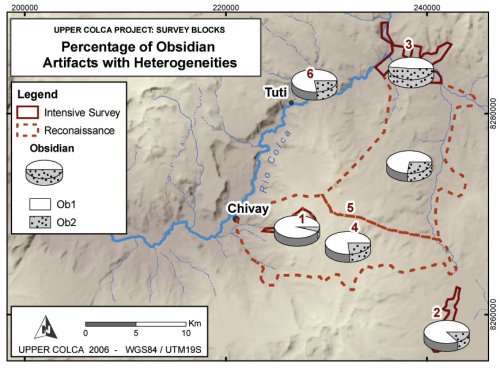

A further line of inquiry relates to the question of presence of heterogeneities in the obsidian. The Block 1 area with both the quarry pit, and the greatest abundance of large nodules, did not entirely consist of Ob1 homogenous obsidian. Investigating all the artifactual obsidian collected from surface contexts in the course of this project by survey block, a number of general patterns emerge.

Figure 6-3. Proportion of obsidian material as Ob1 and Ob2 (heterogeneities), by count.

|

Homogeneous: Ob1 |

Heterogeneous: Ob2 |

||||||

|

Block |

No. |

% |

m%Cortex |

No. |

% |

m % Cortex |

Total |

|

1 |

355 |

93.2 |

36.6 |

26 |

6.8 |

35.4 |

381 |

|

2 |

329 |

90.6 |

6.1 |

34 |

9.4 |

15.9 |

363 |

|

3 |

96 |

64.9 |

15.4 |

52 |

35.1 |

10.2 |

148 |

|

4 |

140 |

73.7 |

23.0 |

50 |

26.3 |

31.2 |

190 |

|

5 |

172 |

73.2 |

30.8 |

63 |

26.8 |

22.5 |

235 |

|

6 |

17 |

77.3 |

1.2 |

5 |

22.7 |

2.0 |

22 |

|

Total |

1109 |

82.8 |

22.6 |

230 |

17.2 |

21.7 |

1339 |

Table 6-8. Obsidian artifact material type by Survey Block surface collections.

Table 6-8 reveals that a small percentage of Ob2 material was actually found to have been used in Blocks 1 and 2, although the representation of Ob2 material was considerably higher in the other blocks in the survey. On the whole, Ob2 cores are decorticated to the same extent as Ob1 cores, although further upon exploration in Table 6-8) reveals that in Block 2 there appears to be a distinct preference for Ob1 obsidian as cores of this material have only 6% cortex while those of Ob2 have nearly 16% cortex. This is a pattern that might be expected, as the Ob2 obsidian has flaws that both negatively affect knapping quality and affect the visual appearance. However, the pattern is reversed in Blocks 3 and 5 where the Ob2 obsidian is decorticated to a greater extent than Ob1 material. There is a link between the color of the obsidian and the material quality because 45% of the grey obsidian is the Ob2 material, whereas for the other shades of obsidian the Ob2 ratios are smaller (10%-25%).

It was noted that in the Maymeja area of Block 1, unmodified obsidian nodules on the surface were often Ob2 material because they had small gas bubbles in them. Accordingly, it appears that some fraction of the obsidian that was knapped in the Maymeja area was made from this Ob2 surface material because it represented 6.8% of the collections from Block 1. The distribution of Ob1 and Ob2 material at the Chivay source will be further explored below prior to examining the results of the survey work in detail.

Further analysis of Ob1 and Ob2 obsidian types at the Chivay source

Figure 6-4. Photographic comparison of the homogeneous Ob1 obsidian and the Ob2 obsidian with heterogeneities.

Building on the overview of the use of Ob1 and Ob2 obsidian in the preceding section (see Figure 6-3 and Table 6-8 above), further exploration of Ob1 and Ob2 distributions follows. The results show that Ob1 and Ob2 obsidian artifacts in the area of the Chivay source assume patterned distributions over space, and these distributions are probably linked to the use of obsidian for export and for bifacial tool production.

Projectile points made from Ob2 obsidian

Eleven obsidian projectile points (4%) were made from Ob2 obsidian; a surprisingly high number under the operating assumption that fracture and visual quality of the material were important characteristics in bifacial tool production. Briefly exploring these eleven Ob2 projectile points may shed light on the characteristics that guided material selection in prehistory.

Ob2 materials form a much higher percentage (15%) of the obsidian flake surface collection than do Ob2 bifacial tools (4%) of the obsidian tool collection, which suggests that Ob2 material was being knapped but apparently not bifacially retouched.

The projectile points made from Ob2 material tend to have small or low-density heterogeneities that do not appear to greatly affect knapping quality, although visually the pieces appear mottled. These points were found in the south-eastern part of the study area in the San Bartolomé area (including one from a Late Formative excavated context), and in the reconnaissance blocks 4 and 5.

|

ArchID |

Block |

Period |

PPt Type |

Weight (g) |

Length (mm) |

Retouch Index |

|

953.1 |

2 |

M. Archaic |

2c |

4.1 |

38.28 |

0.9375 |

|

820.1 |

2 |

3b |

4.1 |

45.82 |

1 |

|

|

918.1 |

5 |

2c |

6.9 |

48.73 |

0.96875 |

|

|

818.1 |

2 |

Late(2) - T. Archaic |

4f |

2.9 |

31.13 |

1 |

|

231.10 |

4 |

T. Archaic - Late Horizon |

5 |

5.3 |

37.62 |

0.84375 |

|

994.1 |

2 |

5d |

0.5 |

21 |

1 |

|

|

1014.3 |

2 |

5 |

2.5 |

25.52 |

0.9375 |

|

|

1026.9 |

2 |

5 |

1.9 |

Broken |

1 |

|

|

1038.3 |

2 |

5 |

11.3 |

19.9 |

||

|

2061.3 |

2 |

5d |

1.2 |

Broken |

Table 6-9. Projectile Points made from obsidian containing heterogeneities (Ob2).

|

Period |

Ob1 |

Ob2 |

Percent with Heterogeneities |

Total |

|

Middle Archaic |

18 |

3 |

14.3 |

21 |

|

Late Archaic |

4 |

1 |

20 |

5 |

|

T. Archaic - Late Horizon |

221 |

7 |

2 |

227 |

|

Total |

243 |

11 |

3.9 |

253 |

Table 6-10. Ratio of Obsidian Projectile Points with heterogeneities.

Due to low cell counts, conducting a chi-squared test required aggregating the counts from the Middle and Late Archaic Periods. A chi-squared test on the aggregated table (Table 6-10) showed that the difference between projectile points from Group 1: Middle and Late Archaicand Group 2: the Terminal Archaic through the Late Horizonwith respect to the use of obsidian with heterogeneities is very significant (c2= 9.976, .005 > p> .001). It appears that Ob2 was very significantly less used for point production in the later time period.

Note that the material used for projectile point production in Block 2 was at times the cloudy Ob2, and it is likely that this reflects, in part, the availability of this material on the southern and eastern flanks of Cerro Hornillo. However, the vast majority of the Ob2 obsidian flakes are actually found in Block 3, at the site of Taukamayo.

Obsidian source material with and without heterogeneities

A number of the lag gravel deposits encountered in Blocks 4 and 5 of the survey are Ob2 material. Accordingly, obsidian artifacts from these blocks are higher in heterogeneities, indicating that there was a utility for this type of obsidian despite the imperfect matrix of the material. Investigating the distribution of Ob1 and Ob2 material across all obsidian artifacts (primarily flakes) shows that the Ob2 make up approximately one half of the obsidian artifacts even in Block 3 some distance from the Maymeja zone where Ob1 was observed in situ.

The mean size of Ob1 flakes is notably smaller, which suggests that more advanced reduction was occurring on the Ob1 material. There may be some size bias occurring with observations of heterogeneities because small flakes struck from Ob2 nodule will often appear relatively homogenous and clear if few bubbles or particles are included in the glass in that portion of the flake.

|

Homogeneous (Ob1) |

Heterogeneous (Ob2) |

Total count |

|||||

|

Block |

No. |

m Length (mm) |

m Weight (g) |

No. |

m Length (mm) |

m Weight (g) |

|

|

1 |

315 |

40.6 |

18.8 |

24 |

40.5 |

25.4 |

339 |

|

2 |

240 |

25.7 |

3.6 |

21 |

33.8 |

10.5 |

261 |

|

3 |

62 |

30.1 |

12.4 |

32 |

30.1 |

6.2 |

94 |

|

4 |

104 |

35.1 |

18.3 |

38 |

36.8 |

20.7 |

142 |

|

5 |

134 |

23.2 |

6.2 |

43 |

25.5 |

6.5 |

177 |

|

6 |

12 |

25.2 |

3.1 |

3 |

31.7 |

6.0 |

15 |

|

Total |

867 |

30.0 |

10.4 |

161 |

33.1 |

12.6 |

1028 |

Table 6-11. Obsidian: mean sizes of complete Ob1 and Ob2 artifacts, by Survey Block.

These data, show patterns in terms of the mean length and weight differences between Ob1 and Ob2 artifacts. In all blocks, Ob1 artifacts are on average lighter than their Ob2 counterparts except for in Block 3. Furthermore, in most blocks the mean lengths of Ob1 and Ob2 material are very close but as the weights are different and therefore width or thickness must vary between Ob1 and Ob2 material. Further investigation of the metric data shows that, indeed, Ob1 artifacts have narrower and thinner medial measures, on average, than do Ob2 artifacts except for in Block 3 where Ob2 materials are thinner.

It appears that throughout the study region, Ob1 materials were preferentially knapped into artifacts that were narrower and thinner, but not necessarily shorter, than the Ob2 materials except for in Block 3. Ob2 material was much more common in Block 3, as will be discussed below, and it appears to have been used for more immediate butchering needs rather than for production of bifacial tools, a pattern that is consistent with the later date of the Callalli occupation. There is also a possibility of size bias where smaller Ob2 flakes are classified as Ob1 because no heterogeneities were evident in that particular small flake.

Discussion

The larger patterns revealed by these surface collections can be summarized as follows. First, the Ob1 material appears to have been available in the largest sizes in the Maymeja area of the Chivay source. Second, knappers in the Block 2 area appear to have made greater use of the Ob1 material, but for some reason they had smaller starting nodules as is evident from the smaller artifacts with ? 30% cortex. The fact that cortical materials in the immediate consumption area have much smaller sizes than those being derived from the Chivay source suggests that the largest Ob1 nodules were notbeing consumed in Blocks 2 and 3, and one possible explanation is that they were being exported to the larger consumption region.

We can gain further insights into the differential use of obsidian through the patterns associated with Ob1 and Ob2 material. These data relate to question of the importance of transparent, homogeneous obsidian. In Chapter 3 the relative use of Chivay and Aconcagua obsidian at Asana was discussed because it was inferred that later pastoralists may have been satisfied with Aconcagua material because they were less concerned with the aesthetic qualities of obsidian and more focused on its utility for shearing and butchering. The assumption being that visual quality was less significant for utilitarian applications. For projectile point manufacture, however, Ob1 obsidian appears to have been much preferred by pastoralists. In the pre-pastoral Archaic the use of homogeneous, Ob1 obsidian for projectile point manufacture was less prevalent.

The use of Ob2 can be considered in terms issues of access, aesthetics, and economy.

(1) Access:The obsidian with heterogeneities was found scattered across a larger region on the east and south-east flanks of Hornillo, as well as intermittently on surface elsewhere in the Blocks 1, 4, and 5 survey areas. In contrast, the Block 1 Maymeja area was the only zone with large nodules of Ob1 obsidian available, and under modern conditions the majority of these are beneath a layer of ash. These data suggest that obsidian procurement during the Middle and Late Archaic may have involved more frequent exploitation of surface materials simply because these groups did not have knowledge of, or need to, excavate to obtain Ob1 obsidian. Alternately, during the Terminal Archaic and onwards, quarrying for clear obsidian in the Maymeja zone was developed and greater quantities of clear obsidian were circulating.

(2) Aesthetics:The Ob1 obsidian appears, to modern eyes, that it would have had more value in cultural and prestige related functions. From a biological adaptationist perspective, Ob1 obsidian has higher costly-signaling value (Craig and Aldenderfer In Press), and one would expect both hunter-gatherers and pastoralists to emphasize obsidian free of heterogeneities for its signaling value. As was discussed previously, exchange of objects between individuals or groups as symbolic tokens is documented among hunter-gatherers as well as pastoralists. However, during the pastoralist period social hierarchy increases rapidly and under these circumstances it is possible that the social importance of Ob1 obsidian to a competitive leader during a period of dynamic transegalitarian is considerable.

(3) Economics:Pastoralist producers of projectile points could afford to be selective in the material that they used because projectile points were not necessarily "consumed" by subsistence hunting. If obsidian points are to be used as the principal means meat procurement, points will be broken and lost during hunting forays and there is therefore a need for less costly and easily replaced projectile points. During the pastoralist period, however, hunting for meat is supplementary to the meat available from the herd. Therefore, projectile point use becomes more discretionary because points are used for activities such as non-essential hunting, warfare, or symbolic exchange.

An additional economic component to the use of clear obsidian concerns the economy of projectile point production. Evidently obsidian was predominantly used for Series 5 (concave base, triangular) projectile points styles, and Series 5 points are much smaller on average than other projectile points. When only unbroken projectile points are considered, the mean weight of series 1 through 4 projectile point types is 5.69 g, sd = 4.92, while for Series 5 points the mean weight is 2.08 g, sd = 1.80. On average, Series 5 points are 2.89 times smaller than the other point styles, and therefore one could produce many more projectile points from a single nodule of clear, Ob1 obsidian if one were to make Series 5 points as opposed to an older, larger type of projectile point.