3.6.1. Variability in Andean obsidian use

In many regions of the world prehistoric artifacts made from obsidian can be generally classified by whether the principal function is for display or for some utility more directly related to subsistence. In Mesoamerica and the ancient Near East, both areas with complex societies and elaborate stone tool production, obsidian was used to make bowls, vases, eccentrics, seal stamps, statuettes, and tables, as well as items of personal decoration such as labrets, ear spools, necklaces, and pendants (Burger, et al. 1994: 246). Craftspeople also developed efficient, high utility obsidian technologies as well, such as prismatic blades, a form that allows archaeologists to quantify cutting edge to edge-length, error rates, and other efficiency measures.

In the south-central Andes the diversity of artifact forms made from obsidian is relatively low, and it is difficult to differentiate display from utilitarian applications. For example, obsidian projectile points are both sharp and highly visible, suggesting that the points had a display function that underscored their utility as a weapon and as a cutting tool.

Hafting in the Andes

Archaeological evidence shows that bifacially flaked obsidian implements were hafted in a variety of ways. The majority of the hafting evidence from the Andes comes from coastal sites due to superior preservation. Projectile points were hafted to spears, spear thrower darts, and arrow shafts. Obsidian bifacial tools were also hafted to wood or bone handles for use as knives. Hafting materials varied regionally, but hafting was often accomplished using gum or resin, and hafts supported with cotton string have been found in some coastal sites (Carmichael, et al. 1998: 79).

Evidence of use of obsidian

The artifact types predominantly manufactured from obsidian include projectile points and tools for cutting and shearing tasks. While simple flakes are wide-spread and were probably used abundantly for butchering, scraping, and shearing purposes, the utility of obsidian flakes is frequently discounted when flakes are relegated to the "debitage" or "debris" class. In Andean studies bifacially-flaked instruments are the most commonly analyzed obsidian artifact class in archaeological reports from sites in the Andes.

Obsidian artifacts are sometimes found in association with iconographic representations of dark colored artifacts that are similar in appearance to the very obsidian artifacts found in that context (Burger and Asaro 1977: 15). Such is the case with black-tipped darts and knives depicted on Ocucaje 8 through Nasca 6 ceramics and textiles, and obsidian artifacts found in tombs from those contexts. Building on the discussion in Burger and Asaro (1977: 13-18), examples of obsidian artifacts from the south-central Andes follow.

|

Application |

Form |

Provenience |

Description |

Reference |

|

Weapon (probable dart point), conflict |

Point |

Looted tomb at Hacienda Mosojcancha, Huancavelica. |

A point made from obsidian was found embedded deeply in a human lumbar. (Figure C-10). |

|

|

Weapon, with spear throwers |

Point |

Grave 16 at Asia, Preceramic context. |

Found in association with spear throwers |

|

|

Weapon, hafted |

Point |

Tombs at Hacienda Ocucaje, Epoch 10. |

Points hafted with gum and, in one case, cotton thread to wooden foreshafts. |

|

|

Weapon |

Point |

Carhua (south coast , Peru) |

Point penetrating through arm muscle near humerus (Figure C-1). |

|

|

Weapon, dart |

Point |

Paracas Necropolis |

Well-preserved harpoon (Figure C-9). |

|

|

Weapon, dart |

Hafted projectile depiction |

Nasca Phase B1 and B2 diagnostic attribute |

Phase B has "Atlatl darts (arrows) in series as ornaments" (Figure C-6). |

|

|

Weapon, poison |

Point |

Eastern Lake Titicaca |

Obsidian is among point types dipped in strong poison from herbs, perhaps curare. |

|

|

Weapon, bow and arrow |

Point depiction |

Tiwanaku pottery |

Archers with bow and black tipped arrows depicted on a Tiwanaku q'ero(Figure C-4). |

|

|

Weapon, hunting |

Point depiction |

Nasca B vessel |

Depiction of darts sailing towards a group of camelids . |

|

|

Tool, Ritual |

Knife depiction |

Nasca B pottery |

Black knives associated with taking of trophy heads. |

|

|

Tool, Ritual |

Knife depiction |

Nasca textiles, Epoch 1 of EIP |

Black knives associated with taking of trophy heads. |

|

|

Tool, Ritual |

Knife, hafted |

Early Nasca |

Bifacial knife hafted to painted dolphin palate (Figure C-5). |

|

|

Decorative, Ritual |

Mirror fragment |

Huancayo, Middle Horizon 2 context |

Fragment of obsidian mirror ground and polished to .4 cm thickness. |

|

|

Decorative, Ritual |

Mirror |

Huarmey, Wari |

Mirror mounded in carved wooden hand (Figure C-8). |

|

|

Medical |

Obsidian knives with blood-stains. |

Cerro Colorado, Paracas |

Part of medical kit that also contained a chachalote (sperm whale) tooth knife, bandages, balls of cotton, and thread. |

|

|

Medical |

Chillisaa kala, Aymara for "black flint" |

Titicaca Basin |

Speculation about tools used for trephination. |

Table 3-10. Examples of obsidian use in the south-centralAndes (part 1).

|

Application |

Form |

Provenience |

Description |

Reference |

|

Medical, |

Material used in folk cures |

Canchis, Cuzco; and elsewhere |

Modern use in folk cures, the stone was believed to have curative powers. |

|

|

Medical, |

"knives of crystalline stone" |

Titicaca Basin ( ?) |

Abdominal surgery by "sorcerers" |

|

|

Animal castration |

Flakes, unmodified or retouched |

Colca |

"We use sharp pieces of obsidian or glass to castrate herd animals it doesn't cause infection like rusted metal knives." |

T. Valdevia 2003, Pers. Comm. (my translation). |

|

Shearing |

Flakes, unmodified or retouched |

Andes |

"Aboriginal shearing required special implements, perhaps obsidian knives." Some modern pastoralists use broken glass and tin lids for shearing. |

Table 3-11. Examples of obsidian use in the south-centralAndes (part 2).

Many of these examples are shown in Appendix C. of this volume. While the diversity of artifact forms was relatively low, it is evident that the visual and fracture properties of obsidian were relevant to the tools that were used from this material. Further north in the Andes, in Ecuador, a greater percentage of obsidian artifacts seems to have filled a primarily decorative role, including abead, an ear spool, and three polished mirrors(Burger, et al. 1994: 246).

The evidence of use lithics may also take the form of cutting and scraping marks on faunal remains, but the lithic material type can rarely be established by these means. The continued use of glass and obsidian in modern contexts for shearing, butchery, and castration suggests that the prehispanic metals such as copper and bronze did not displace obsidian and other lithic materials for utilitarian tasks. Prehispanic metals were used largely for display, although metals were used in some weaponry, such as mace-heads (Lechtman 1984).

Obsidian in warfare

The evidence for obsidian use in conflict in the Andes comes from a variety of archaeological and ethnohistorical sources, but it is primarily in the form of indirect evidence. The data reveal a great expansion in the production of small obsidian projectile points after the onset of a food producing economy. The majority of Late Horizon weapons that the Spanish faced during their invasion appear to have been bola stones and percussion weapons like maces and slings(Cahlander, et al. 1980;Korfmann 1973), as well as padded armor.

Archaeologists working in the south-central Andes vary historically in their assessment of the use of projectiles in the highland region(Giesso 2000: 43). Bennett(1946: 23)asserts that the use of bow and arrow were not important on the altiplano, Metraux(1946: 244-245)says that spear throwers were in use, while Kidder(1956: 138)indicates that evidence from projectiles show that arrows were widely used at Tiwanaku. Of the projectile points analyzed by Giesso from Tiwanaku, 19% were made from obsidian, with the highest concentration of points coming from excavations in the civic/ceremonial core at the Akapana East, K'karaña, and Mollo Kontu mounds(Giesso 2000: 228-238).

In a dramatic example of obsidian use as a weapon, one archaeological findError! Reference source not found.shows a probable spear or dart point penetrated the victim's abdomen from the left anterior abdomen and lodged on the anterior side of the lumbar vertebra.

Evidence of use of the bow and arrow in warfare

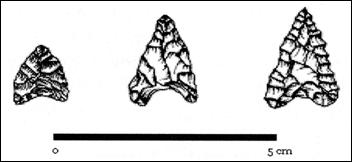

One of the strongest patterns in obsidian distributions in the south-central Andes is the sudden onset of obsidian use with series 5 projectile points in the Terminal Archaic, after 3300 cal BCE In defining the small type 5D projectile points Klink and Aldenderfer(2005: 54)suggest that the widespread adoption of these point types may reflect the use of bow and arrow technology, as these points fallwithin the size range described by Shott (1997: Table 2) as associated with arrow points (although with substantial overlap with the size of the smaller dart points).

Figure 3-14. Type 5d projectile points from a Terminal Archaic level at Asana and Early Formative levels at Qillqatani, from illustration in Klink and Aldenderfer (2005: 49).

Additional metrics for differentiating arrowheads from dart and spear points have been suggested by Thomas (1978: 470) and Patterson (1985). With Mesoamerican projectile points, Aoyama (2005: 297) has found a very significant correlation between evidence from microwear analysis and projectile dimensions in his effort to differentiate arrowheads from dart and spear points. The relationship between the mass of the item and the velocity and distance of the projectile are discussed in detail by Hughes (1998). She notes that the innovation of fletching allowed for balanced projectiles that had smaller projectile tips and lighter shaft materials, which in turn permitted greater distance and velocity in weapons systems (Hughes 1998). On a related point, the notched base in all type 5 projectile styles reflects a change in hafting technology. Greater impact loads can be absorbed by mounting projectiles tips with notched bases into slotted hafts (Hughes 1998: 367;Van Buren 1974).

Obsidian has a number of attributes that make it a particularly effective material for projectile point tips, most notably are the predictableconchoidal fracture qualities of obsidian that allow it to be pressure flaked into very small projectile points. The sharpness of freshly knapped obsidian margins is unrivalled, andethnographicallyobsidian is renowned as a brittle material that can fracture on impact, causing the fragments to produce greater bleeding in the victim of an obsidian projectile (Ellis 1997: 47-53). In materials science, obsidian has extremely low compression strength because it has no crystalline structure (Hughes 1998: 372). Due to the brittleness or lack of compression strength, missed shots can result in many broken obsidian projectile tips, and perhaps for this reason obsidian was not the predominant material for projectile point production until after the domestication of camelids when hunting was decreasingly the primary source of meat (as inferred from the ratio of camelid to deer bone in excavated assemblages).

Increased velocity and distance is possible with the use of bow and arrow, and obsidian has greater penetrating power, although lower durability, than other material types. Do these changes suggest a greater use of projectiles for warfare? Greater use of small, fletched projectiles might be expected in contexts where the individual needs (1) increased distance from the target (2) increased velocity, perhaps due to change in prey or to the use of padded armor. The use of obsidian may increase in contexts where one needs (1) a material that can be knapped into small, light projectiles as discussed above, (2) increased penetration with sharper material, (3) decreased concern for durability because in warfare the weapon will perhaps be retrieved by the opponent.

Although empirical evidence for warfare is scarce in the Terminal Archaic in the highlands, a study of 144 Chinchorro individuals from Terminal Archaic contexts in extreme northern Chile found that one third of the adults suffered from anterior cranial fractures that probably resulted from interpersonal violence, and men were three times more likely than women to have these wounds (Standen and Arriaza 2000). These wounds appear to have been caused by percussion weapons like slings, but the coastal evidence for interpersonal violence in this time period is strong. Additional support for the introduction of the bow and arrow in the Terminal Archaic come from the region among Chinchorro burials in coastal Northern Chile. Bows among the Chinchorro grave goods date to circa 3700 - 1100 cal. BCE, or the Terminal Archaic and Early Formative (Bittmann and Munizaga 1979;Rivera 1991;Standen 2003).

Possible use of poisons on projectile tips

A potential explanation of widespread adoption of the small type 5D projectile points is the greater availability of poisons that reduced the need for heavy, destructive projectiles.South American poison arrows are usually quite small and such arrows are frequently tipped only with a sharpened wooden point. According to Ellis(1997: 55),virtually all ethnographic examples of arrow use include some kind of poison applied to the arrow in order to have either a toxic or a septic effect on the victim. Ellis observes that due to the great variety of substances used to create such toxins, in many regions of study these substances would probably contaminate any chemical attempt to use residue analysis to differentiate the types of poisons used, or even the prey that was hunted, with a particular used projectile point.

A variety ofhighly effective poisons are applied to the tips of projectiles by hunters in the Amazon Basin today(Heath and Chiara 1977).In the prehispanic Andean highlands, trade contacts with the Amazonian lowlands to the east may have made available poison concoctionsfor application to projectiles, most notoriously the fast acting paralysis alkaloid curareprepared from the vine Chondrodendron tomentosum(Casarett, et al. 1996).

Bernabé Cobo (1990 [1653]: 216-217) discusses the use of bow and arrow with poisons by "expert marksmen" in his chapter on warfare. Hedescribes the widespread and expert use of the sling for warfare, which is consistent with reports elsewhere on the use of slings, but then he states that bow and arrow were more significant in warfare.

The most widespread weapon of all the Indies, not only in war but also in the hunt, was the bow and arrow. Their bows were made as tall and even taller than a man, and some of them were eight or ten palms long, of a certain black palm called chontawhose wood is very heavy and tough; the cord was made of animal tendons, cabuya, or some other strong material; the arrows, of a light material such as rushes, reeds, or cane, or other sticks just as light, with the tip and point of chontaor some other tough, barbed wood, bone, or animal tooth, obsidian point, or fish spine.

Many used poisoned arrows, their points anointed with a strong poison; but, among the nations of this realm, only the Chunchosused this poisonous herb on their arrows, and it was not a simple herb, but a mixture of various poisonous herbs and vermin; and it was so effective and deadly that anyone hit by one of those poisoned arrows who shed blood, even though it might be no more than the blood resulting from the prick of a needle, died raving and making frightful grimaces(Cobo 1990 [1653]: 216-217).

The Chunchos ethnic group is described as living in the "forests east of Lake Titicaca on the border of the Inca Empire".It is possible that Amazonian poisons became available in altiplano during the Terminal Archaic due to expanding exchange networks, together with Amazonian hallucinogenics and other lowland products, dramatically altering the efficacy of arrows. As a sharp but lightweight weapon, obsidian tipped arrows would have represented an effective poison delivery system to animal and human victims alike.

While there is no direct evidence for the use of Amazonian poisons on the altiplano, the dramatic change in projectile technology with the type 5D type, co-eval with expanding exchange networks in the region, suggest that a new technology for weapons systems, such as poisons and new shaft and fletching materials, may have influenced the design of projectiles in this time.The transitional economic context of the Terminal Archaic involved many changes, including shifts in both food production and interregional exchange, and the technology of lithic production show significant alterations that correspond to this period.

Multiethnic access to geological sources in the Andes

Salt procurement in the Amazon basin on the eastern flanks of the Andes provides an example of multiethnic access to a raw material source. During annual voyages to the Chanchamayo salt quarry ten days outside of their territory, the Asháninka of the Gran Pajonal (Ucayali, Peru) combine salt procurement with exchange with neighboring groups who share access to the source(Varese 2002: 33-35). Arturo Wertheman, a missionary who traveled through the region in 1876, explains

Throughout the year small bands of Asháninka traders traveled [the Gran Pajonal] paths to obtain salt, carrying with them tunics or ceramics to exchange for other items and for hospitality. With them traveled their traditions, their hopes, and the information of interest to their society. The Pajonal, the vast center of Campa territory not yet invaded by whites, appears to have been the center of culture and tradition through which the Indians journeyed, like a constant flow of life through their very society(Varese 2002: 120)

Other ethnographic examples of multiethnic access to salt quarries are mentioned in the ethnographic literature. Oberem(1985 [1974]: 353-354)describes access by both the Quijo and the Canelo people to a large rock salt quarry located on the Huallaga River, a tributary to the Amazon lying further north on the border of Peru and Ecuador.

In the Cotahuasi valley of Arequipa, to the north of the Colca valley, the rock salt mine of Warwa [Huarhua] has been exploited since Archaic times(Jennings 2002: 217-218, 247-251, 564-566). Access to the Warwa quarry, which lies near the border of the departments of Arequipa, Ayacucho, and Apurímac, is described by Concha Contreras(1975: 74-76)as including caravan drivers from all three of those neighboring departments.

El primer viaje lo hacen, mayormente, en el mes de abril. En esta época cientos de pastores se concentran en esta mina. El camino es estrecho y accidentado hasta llegar a la misma bocamina…Desde el fondo de la mina los pastores cargan a la espalda la cantidad de sal que necesitan llevar, de tal manera que hacen muchos viajes al socavón de la mina. En todo este tramo tardan 4 días, porque después de la mina, siguen cargando en la espalda hasta una distancia de aproximadamente cinco kilómetros, donde quedaron las llamas pastando, puesto que hasta la misma mina no pueden entrar juntamente con sus llamas(Concha Contreras 1975: 74).

There appear to be a number of protocols associated with salt acquisition at Warwa. Notably, the multiethnic visits by caravanners from various departments coincide in April despite the tight working quarters at the salt mine. Furthermore, there seems to be concern for impacts in the much-visited the mine area itself. The cargo animals are actually grazing a distance from the quarry and humans are obliged to carry the loads to these areas instead of attempting to load the animals close to the mine. These cases of multiethnic raw material access provide examples of the social and institutional nature of access to unique geological sources, and the focalized attention that these source receive from surrounding ethnic groups. The analogy with regional acquisition and diffusive transport of the raw material is perhaps the closest modern analogy to the nature of prehispanic obsidian quarrying that remains in the Andes.