2.4. The View from the Quarry

For over one hundred years archaeologists in the Americas have noted the potential of studying quarries, yet consistency is lacking in the approaches that have been taken, making it difficult to compare quarrying behavior cross-culturally. The principal theoretical objective for quarry studies in many parts of the world is establishing a link between models of social change and the extraction of resources at a give quarry through time. Despite the productive research into quarrying during the early part of the twentieth century, quarries worldwide have received insufficient attention by archaeologists.

Beginning with the pioneering work of William Henry Holmes (1900;1919), archaeologists have recognized that the remains of quarrying and mining have the potential to provide valuable information about the past. Holmes' work was a major contribution as he discussed the broad issues of the geographic locations of known quarries and workshops, artifact manufacture, the quantities of waste material, and the use of fire in quarrying. The sole major component of modern quarry studies that Holmes did not explore was technical flake analysis, which wasn't developed yet, and a discussion of the chronology of the use of the quarries, which was very difficult to achieve prior to radiocarbon dating.

With the development of geochemical sourcing methods during the 1960s that linked materials with certainty to their geological source areas, quarry studies began to be of greater interest. The goal of most quarry studies is, through a combination of evidence from the resource procurement and the consumption contexts, to examine changes through time in the mechanisms of exchange that link the production and consumption together. These mechanisms are believed to reflect the prevailing organization of the stone tool economy.

A central challenge in conducting archaeological research at quarries is that at the typical raw material source, due to the sheer volume of archaeological materials and the variability in procurement contexts in prehistory, it is vital to have a clear research strategy. By targeting research questions and theoretical goals, and then determining the appropriate sampling methods, the abundance of material at a quarry can be approached with a few specific guiding questions to be answered, as well as an eye for new, unanticipated findings. Several researchers have discussed frameworks for studying the ancient quarrying of stone. Torrence describes the rich potential of studying production and exchange from the perspective of the quarry in terms of the unique position of the quarry for the study of a "complete exchange system" (Torrence 1986: 91, see Section 2.2.5).

These frameworks for quarry research fall into three sets of approaches, corresponding roughly to major theoretical groups in archaeology, and most will use a combination of these approaches emphasizing (1) efficiency, (2) social factors, and/or (3) ideology. The theoretical approach taken is often conditioned by the available data. For example, an ideological approach is strongest when demonstrable ethnographic, historical, or archaeological data are available that display a clear ideological basis for behavior concerning the stone tool procurement. Similarly, efficiency and error rates are more measurable from some reduction strategies, like prismatic blade production, and therefore cost minimizing analyses are very fruitful with such data.

2.4.1. The specialization and efficiency framework for quarry studies

The most thoroughly-articulated efficiency model is the one developed by Torrence during her dissertation work on the Greek island of Melos (Torrence 1981;Torrence 1986). Her approach at the obsidian quarries of Melos focuses on lithic reduction sequences in order to detect the changes in morphology of flakes that point to increased specialization due to standardization of reduction strategies. Her goal is to establish "a framework for measuring exchange" by developing a continuum for production efficiency that aims to link particular levels of efficiency with the social correlates that indicate the existence of different forms of exchange. Citing Rathje (1975: 420-430), Torrence approaches the study of long-term changes in the efficiency of extraction and manufacture in terms of sophistication of technology, simplification, standardization, and specialization (Torrence 1986: 42). In her research she is able to establish a continuum of efficiency starting with the irregular, non-specialist production on one end, and high efficiency production characterized by ethnohistorical evidence from modern gunflint knapping, on the other end.

Characteristics of prismatic blade production facilitate the kind of examination for efficiency and specialization used effectively by Torrence. First, core-blade reduction sequences leave relatively visible evidence of the technical stages for archaeological analysis. Secondly, prismatic blades are extremely efficient as measured experimentally using cutting-edge to weight ratios (Sheets and Muto 1972). Finally, archaeologists have developed measures of error rates for obsidian blade production with the aim of establishing the degree of knapping expertise from debitage, and these measures correlate with efficiency gauged in both time and consumption of material (Clark 1997;Sheets 1975). These efficiency measures are relevant in areas with blade production, but they are not applicable to research in areas with exclusively bifacial reduction traditions, such as in the south-central Andes.

The efficiency measures that Torrence develops in her approach linking production with exchange has the advantage of being explicit and comparable across regions. Further, her measures of production efficiency complement the formal assumptions that underlie the fall-off curves used to analyze regional exchange models in an evolutionary approach that projects greater efficiencies in organization through time. That is, specialized blade production is the most efficient means of producing cutting implements, and freelance trade in a market based economy, following Polanyi's schema, is the most efficient means of moving goods to consumers. Efficiency measures have heuristic value, as divergences from expected efficiency models can prompt the pursuit of theoretical inquiries into the cause of the deviance from the anticipated efficiency models.

The most problematic aspect of this framework is the dependence on the theoretical link connecting efficiency measures to prehistoric institutions (Bradley and Edmonds 1993: 10), particularly in light of the substantivist/formalist debate in anthropology specifically referencing gifting and exchange relationships. Bradley and Edmonds (1993: 10) observe that, as with Renfrew's regression approach, the problem of equifinality undermines the system of inference when the principal link between production efficiency and elaborate institutions is reduction evidence from workshops. They question the supposition that larger socio-political structure and evolutionary stages can be reconstructed from the limited perspective of workshop production and regional distribution patterns based largely on consumption sites that often have poor temporal control and few contextual associations.

More recent studies have pursued another direction and have avoided comprehensive formal "frameworks" in favor of more willingness to incorporate case-specific details, social dynamism, and historical factors in developing social models of exchange (Friedman and Rowlands 1978;Hodder 1982).

Formal, cost-minimizing assumptions about human actions and incentives have provided archaeologists with a much-needed analytical structure to the study of prehistoric exchange, but critics note that it cannot provide a complete picture of ancient economies.

As Hodder notes, most studies have been predicated on the idea that progress can be made by assuming that people in the past considered costs and benefits along formal economic lines (Hodder 1982). Torrence's (1986) study is a case in point, for it is only by making this assumption that she is able to apply the same scale of measurement to people as different from one another as hunter-gatherers procuring workable stone for their own use, and the makers of gunflints for sale in the modern world market (Bradley and Edmonds 1993: 10).

A formal approach can serve as one of the layers in a more comprehensive analysis that also integrates finer scale social factors as well as historical particulars into the analysis.

2.4.2. Analysis of a production system

In a multi-tiered approach that examines evidence from workshops, from residential sites in the vicinity of the quarry and finally lithics from more distant, consumption contexts, Ericson (1984) describes a general "Lithic Production System".

|

Name |

Variable (numerator) |

Normalizer (denominator) |

Unit(s) |

|

Exchange Index |

Single source |

Total material |

Count, weight, % |

|

Debitage Index |

Debitage |

Total Tools and debitage |

Count, weight, size, % |

|

Cortex Index |

Primary and secondary reduction flakes |

Total debitage |

Count, % |

|

Core Index |

Spent cores |

Total cores and tools |

Count, % |

|

Biface Index |

Bifacial Thinning Flakes |

Total debitage |

Count, % |

Table 2-5. Measurement indices for procurement system (after Ericson 1984: 4).

The indices presented by Ericson depend upon general artifact type categories and provide a basis for comparing activities between workshops, local sites, and distant consumption locales. Note that Ericson did not separate complete flaked stone artifacts from broken artifacts, as this was the early 1980s, and thus his resulting indices using weight measures were likely skewed.

The measures in Ericson's table emphasize the goal of allowing comparability between archaeological datasets over widely studied areas by principally relying on general metrics that are commonly gathered in laboratory analysis. In contrast, the current Upper Colca study employed technical analyses of complete flakes and cores in order to highlight differential reduction strategies between assemblages, or between bifacial core versus flake-as-core reduction.

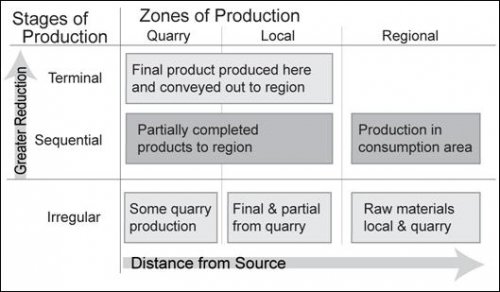

Figure 2-6. Stages of production from quarry, local area, and region (after Ericson 1984: 4).

Ericson presents the spatial distribution of lithic production in terms of stages of production and zones of geographic proximity to the source area. A consistent implementation of this approach on a local and regional scale requires the sourcing (visually or chemically) of the lithic material. Despite the use of commonly gathered measures in indices of production, it would be necessary to ensure that relatively consistent practices in excavation and analysis procedures were in place to permit this kind of regional comparability.

Ericson asserts that workshops should be studied on a general level rather than pursing spatial and temporal variation in activities at the source. He writes that if "there are a number of different workshops at the source, the data must be merged to form a composite picture of production" (Ericson 1982: 133). The emphasis is on documenting the predominant production strategy at a given source area, but at the cost of characterizing variability within a production context. If changes in the use of a given material have been differentiated from stratified deposits at consumption sites in the larger region, how are these changes to be linked with production activities? While workshop sites often lack datable materials or temporally diagnostic artifacts, collapsing all excavated workshop data, and perhaps surface evidence as well, into a single composite picture sacrifices the detail that stratified deposits can provide.

Excavation and analysis procedures in Ericson's California dataset appear to be relatively consistent for the past half-century, however the systematic collection and analysis of non-diagnostic lithics has been historically deemphasized by archaeologists in some regions of the world, such as the south-central Andes. Archaeological practices worldwide have not placed equal emphasis on gathering and quantifying lithic artifacts which would lead to problems in applying the kinds of metrics Ericson suggests on a regional scale. Ericson's approach emphasizes the use of quantifiable and comparable measures over a geographically extensive region.

Barbara Purdy (1984) emphasizes chronology in her study of a chert procurement site in Florida. She did not find datable, organic remains in association with stratified excavations that would provide greater evidence of the temporal associations, but the strata in her test units allowed her to differentiate distinct episodes of use of the site. She found that weathered chert artifacts in a sandy-clay soil were separated by a lithologic discontinuity from less-weathered artifacts produced using a different technology. She was also able to use the relative weathering of chert and thermoluminescent dating on fire-altered chert cobbles from the quarry site.

2.4.3. Specialization at a Mexican Obsidian workshop

Obsidian quarry workshops at Zináparo-Prieto in the state of Michocan in western Mexico were investigated comprehensively by Veronique Darras (1991;1999). Darras undertook excavation as well as systematic survey of vicinity of the substantial quarry area that was used most intensively during the Classic to Post-classic transition (A.D. 850-1000). She documented mines and workshops, as well as associated residential structures and public buildings, in an inventory of 45 sites in the region.

Darras describes mine shafts and open-air quarry pits that parallel obsidian procurement methods elsewhere in Mesoamerica. The mine shafts (Darras 1999: 72-80), are over 25m in depth and include support pillars as well as evidence of torch lighting and ventilation shafts, can be compared with Classic and Post-classic period mining methods used at other Mexican quarries that include the Sierra de las Navajas (Pachuca) source in Hidalgo (Pastrana 1998), and the Orizaba mines (Cobean and Stocker 2002). Open-pit quarry depressions are reported by Darras at Zináparo-Prieto that measure between 10-15m in diameter, with a few larger than 15m in diameter. Quarry depressions with an encircling debris mound were described by Healan (1997) at the Ucareo source, also in Michocan, as "dough-nut quarries".

The lithic analysis approach used by Darras, citing the tradition of Tixier (1980), addresses the abundance of material (the typical problem with quarry research) by employing two levels analysis (Darras 1999: 108-115). The first measures abundance using a relatively expedient typological classification based on material quality, technical class, reduction stage, and relative size and form of artifact. The second level of analysis, conducted only on a representative samples, consists of a techno-morphological analysis of flakes including a detailed study of platform characteristics and fracture and termination types.

Darras finds no evidence of pressure flaking or prismatic blade technology, a situation that makes this workshop analysis to be more comparable to reduction sequences elsewhere outside of Mesoamerica where prismatic blade production also did not occur, such as obsidian production the south-central Andes. Darras finds that percussion industries follow two contemporaneous sequences: one that uses "cada plana" (plane-face) cores, and the other that uses conical cores, each sequence meticulously outlined. These twin industries, and the lack of prismatic blade production, are unusual in the region and Darras suggests that this is due to a lack of regional political control during this stage.

Darras succeeds in integrating household archaeology with her workshop studies, and as revealed by comparison with obsidian consumption in an associated village, Darras documents substantially more obsidian production than appears to have been used locally. However, she does not extend her analysis to the immediate region beyond villages adjacent to the quarry areas, leaving a disjunction between reduction evidence from the immediate quarry workshops and the larger pattern of obsidian artifacts radiating into the region. Darras' study is one of the most thorough workshop investigations to date, and her work provided a valuable model for the current Upper Colca project research because in the manner that test excavations were used to connect quarry evidence with initial reduction trajectories at associated workshops.

2.4.4. A contextual approach to Neolithic axe quarries inBritain

A focus on social context is emphasized in more recent studies of exchange. Building on Hodder's (1982) development of a "contextual approach" to exchange, archaeologists following this approach argue that the study of production sites has been incomplete because the social and sometimes historical elements of quarries and production systems have been neglected in processual tradition that focuses overwhelmingly on the organization of technology and production efficiency. In particular, Hodder and others have argued that the perspectives on exchange articulated by Mauss (1925) and even by Sahlins (1972) have been largely neglected (to judge from citation patterns) in the formal approaches previously described.

A study by Richard Bradley and Mark Edmonds (1993) focuses on axe production and circulation in Neolithic Britain through an examination of quarry production at the Great Langdale complex in the Cumbrian mountains in the Lake District of the English uplands. This area was a source for a fine-grained volcanic tuff material used for producing stone axe heads that were flaked, ground, and often polished, and have been found in Neolithic. Through petrographic analysis it has been possible to connect many axes made from tuff and granite found throughout Britain with the raw material source in the Great Langdale region, but subsourcing resolution has not been possible.

Background and methodological approach

Bradley and Edmonds (1993: 5-17) begin with a useful critique of the formal approaches to exchange first articulated in the work of Renfrew and his colleagues. In reviewing prior approaches, Bradley and Edmonds perceive weaknesses and untenable assumptions in the links asserted by prior researchers connecting (1) efficiency in reduction strategies, organization of production, and degree of hierarchy in social organization (Torrence, Ericson, others), and (2) geographical distributions of types of artifacts with the nature of social organization (Renfrew et al.).

Bradley and Edmonds emerge with a strategy that permits them to connect temporal change in quarrying and the organization of reduction in the immediate vicinity of the source with perceived changes in knapping strategies. They also explicitly attempt to incorporate evidence from social and symbolic constraints on quarries, where historical specifics about specialization, quarry access, and socio-political boundaries appear to trump the larger patterns of circulation documented during the 1970s by Renfrew, Hodder, and others (Bradley and Edmonds 1993: 9, 63). Further, the authors observe that while these social and symbolic control variables are extremely difficult to appraise from archaeological evidence, these unknowns were ultimately some of the most important variables informing Torrence's (1986) formal approach to efficiency and socio-economic control of production. On these grounds, Bradley and Edmonds devote more effort to methodological and theoretical goals that they feel are attainable: documenting variability in production, inferring connections with regional consumption evidence through temporal context, and exploring social and symbolic generalities through ethnographic analogy from quarries and with evidence of regional ground axe distributions in Britain.

Technical analysis

Bradley and Edmonds' (1993: 83-104) lithic analysis begins with experimental knapping studies that allow them to identify the character and frequency of different classes of flaked stone generated during production. Establishing reduction stages from flakes of Great Langdale tuff material is particularly difficult because the material does not contain a visible cortex. Bradley and Edmonds pursue strategies that produce a wide range of flake and core morphologies in an effort to capture the range of possible variation in reduction at production sites. Their expressed aims are to move beyond simple measures of efficiency in production, and they also seek to use their experimentally-derived assemblages to inform their analysis such that that they do not merely derive a single, generalized reduction sequence but, instead, shed light on how knappers controlled form, and anticipated and avoided mistakes.

It was just as important to discover which methods couldhave been used to make an artifact as it was to establish which were actually selected. It is clearly important to understand howthe production process was structured in a given context, but we also need to discover whyit took the form it did (Bradley and Edmonds 1993: 88, emphasis in original).

In earlier work Edmonds (1990) cites from, and applied, the chaîne opératoireapproach to his investigation of quarry production. Curiously, in the Bradley and Edmonds (1993) volume the French term does not appear (although they cite the chaîne opératoireliterature), and in their quarry production studies they instead choose terms like "pathways" to describe sequential reduction.

Part of Bradley and Edmonds' aim is to reintegrate symbolic and social perspectives into the study of quarry production and exchange, empirical archaeologists may ask: how do Bradley and Edmonds conduct symbolic and social analysis with lithic attribute data from a quarry workshop? In their data-oriented investigation of reduction strategies, Bradley and Edmonds gather standard lithic attribute data that is largely in common with those that follow the processualist tradition; it is in the interpretations and assumptions about economy that the differences emerge. For example, many of the assemblages are described by Bradley and Edmonds along a production gradient that range from "wasteful and inefficient" to "careful preparation" or ad-hoc versus structured production using evidence from flake dimensions, platform morphology and preparation, flake termination type, and other attributes.

For Bradley and Edmonds, efficiency is investigated primarily in a heuristic manner in association with spatial context in that they suggest expediency, investment, and reduction strategies over the larger quarry area. Their technical analysis is able to conclude, among other things, that axes appeared to be exported from the quarry area in two forms: (1) crude asymmetrical rough-outs with hinges and deep scars, and (2) more processed and nearly finished artifacts that lacked only polishing.

They also note that some processing appeared to occur at some distance from the quarry, and in other cases nearly all of the production sequence occurs at the quarry. The authors used evidence of excessive labor expenditure, such as in axe grinding and polishing, as a contrast to the "rational", cost-minimizing expectations of efficient production expectations. For example, they explain that polishing of axe heads is laborious, but it results in greater longevity in the axe because during use the irregularities can act as platforms for unintentional flake removal. Furthermore, polished axes remain in their hafts more consistently. Polish over the entire surface, however, is not necessary and is labor intensive. Were axes polished over their entire surface to increase their exchange and gift value through greater labor investment? In evolutionary approaches, labor investment in goods is cited as a form of prestige technology (Hayden 1998, see Section 2.2.2). Bradley and Edmonds present an insightful review of existing approaches and bring quarry analysis one step further with their in-depth technical analysis that informs a novel yet cautious interpretation with an incorporation of elements of the symbolic and social theory current in the early 1990s.

Chaînes opératoires at quarry workshops

The chaîne opératoireanalysis of quarry materials described by Edmonds (1990) deserves further mention. The chaîne opératoireapproach conceives of lithic reduction as a comprehensive system or "syntax of action" from the origin of lithic material at the quarry to reduction, reuse, and abandonment within a larger context of human action. Sellet (1993: 106) writes that the chaîne opératoireis a "chronological segmentation of the actions and mental processes required in the manufacture of an artifact and its maintenance in the technical system of a prehistoric group. The initial stage of the chain is raw material procurement, and the final stage is the discard of the artifact."

In the realm of lithic production, Shott (2003) and others question whether the chaîne opératoireapproach is notably different from Holmes' century-old concept of "reduction sequence" (Holmes 1894) and Schiffer's Behavioral chain analysis (Schiffer 1975). Two major differences distinguish chaîne opératoirefrom the lithic reduction sequence analysis in the North American tradition. First, while the American reduction sequence focuses solely on lithic production, chaîne opératoireapplies to apprenticeship and expertise relating to allmaterial culture behavior beginning with lithic production but also including ceramics, textiles, architecture, wine-making, and others (Tostevin 2006: 3). Second, even when confined to lithic production, the chaîne opératoireapproachexplicitly attempts to infer the choices and intentionality of the knapper, as well as to capture greater context and breadth by seeking to address the larger context of activity and action.

French archaeology has a long tradition of attributing archaeological variability to choice, stretching back from Boeda (1991) to Bordes to Breuil. This tendency is balanced by an equally strong American-based resistance to attribute variation to cultural choice until all other factors, particularly reactions to environmental stimuli, have been excluded, forming one of the central tensions in the current debate (Tryon and Potts 2006).

Others argue that while attempts to consider the intentionality of the knapper are commendable, in their weaker form sequential models like chaîne opératoirerun the danger of being overly typological and rigidly unable toincorporate behavior that diverges from a one particular linear progression (Bleed 2001;Hiscock 2004: 72).

From the perspective of quarry procurement and workshop activities, production would have proceeded with a goal in the mind of the knapper based on the quality of the raw material as well as organizational issues like technological requirements and mode of transport. For Edmonds (1990: 68) implementing a chaîne opératoireapproach at a quarry workshop appears to have been complicated by an overwhelming presence of flaked stone belonging to early stages production, and a paucity of evidence concerning consumption. It seems that observing a complete "syntax of action" is hampered by the incomplete view of reduction, as the evidence is overwhelmingly from workshops and not from consumption sites. Thus, while quarry workshops have relatively few classes of artifacts the techniques, such as refitting, are seldom practicable when there is an abundance of early stage material and an under-representation of advanced reduction flakes and complete, or near complete, tool forms.

Variability in initial reduction of cores observed at the Great Langdale quarry workshops reflect the available raw material and the quarrying methods used to procure the material, and these frame the starting context for following a chaîne opératoireanalytical model. However, the chaînesequence is often truncated and largely capable of merely determining early reduction characteristics that are basic to all reduction sequence analyses in the tradition of Holmes (1894). For example, at Great Langdale the researchers determine, mostly from platform characteristics, that there was expedient, ad hoc production in one period and more precise and controlled flaking in another. Sequence models seem to be of limited utility in contexts where only initial workshop production is available, a condition that perhaps explains the avoidance of an explicitly chaîne opératoireapproach in the later Bradley and Edmonds (1993) volume. In sum, chaîne opératoireis roughly synonymous with American 'reduction sequence' and Schiffer's Behavioral Archaeology in terms of low and mid-level theory, but in high level theory it is not generally presented except for the theory of chaîne opératoireitself (Tostevin 2006). Given the difficulties of meaningfully applying chaîne opératoireto data based almost entirely on quarry workshop contexts, the concepts will not be attempted in this research.

Interpreting the axe trade

While earlier approaches focused on efficiency and evolutionary schema in a commodified vision of production, Bradley and Edmonds (1993) attempt to take a middle road where they use measures of efficiency and investment observed in workshop contexts in a heuristic manner, but they principally base their interpretations of production on the changing socio-political context of the larger consumption zone. They consider artifacts in terms of dichotomies that probably existed in some form, dividing the circulation of inalienable gifts from alienable commodity production. They seek to consider the implications of gifts in the theoretical terms that relate gift-giving and status acquisition with the political strategizing of elites in Neolithic Britain. Further, they consider the "regimes of value" where gifts and commodities circulate and are assigned value that is a construction of political contexts and not merely a reflection of measurable costs using the concepts of social distance borrowed from Sahlins. Finally, Bradley and Edmonds consider the circulation of axes as wealth goods and the ways in which elites may influence the specialized production of axes (Brumfiel and Earle 1987) and the circulation and consumption in a peer polity situation (Renfrew and Cherry 1986) or through control of deposition (Kristiansen 1984). Ironically, while neoevolutionist approaches are explicitly rejected, one is left with the question: what is theoretically significant about changes observed in the circulation of axes if not the link to evolutionary changes in socio-political organization? In both Edmonds (1990: 66-67) and Bradley and Edmonds (1993), evolutionary explanations are avoided in the analysis of production, but in regional exchange the changes observed attributed to increasing levels of social ranking as indicated by competition over exchange networks and specialized knowledge during the Later Neolithic.

2.4.5. Discussion

The principal challenges of quarry research in archaeology were articulated in the seminal work of Holmes, one hundred years ago. These difficulties include the sheer quantity of non-diagnostic artifacts and sampling issues, the lack of temporal control, and stratigraphy that is either complex or non-existent, it is no wonder that relatively few projects have targeted quarry areas in the intervening century.

Advances in the last few decades include methodological improvements like rigorous attribute analysis and greater standardization of measures and digital measurement devices that have sped up lab work. Theoretical advances include an exploration of principles of production efficiency and subsequent articulation of the problems and prospects of this formal approach. Principal among these are further incorporation of data from adjacent contexts, the use of other lithic material types close to a major source, and the incorporation of evidence from other material classes like ceramics. More recent advances include the incorporation of additional datasets into quarry and workshop analysis, a wider theoretical scope, and an attempt to understand the wider intentionality and decision sequence of quarry procurement and initial production.

A promising theoretical approach to procurement and exchange would recognize the need for a consistent framework against which to assess changes in production, circulation and the regional demand, but it is also one that responds to local variation and multiple reduction trajectories outside the scope of formal concepts of efficiency. Production and circulation of lithic raw material from quarry sites often span broad time periods and must reconcile with a great variety of cultural and organizational forms. In regions of the world (such as the south-central Andes) where foraging was largely replaced by agro-pastoralism, where residential mobility was replaced by sedentary communities with mobile components, and where egalitarian social structure changed into ranked and ultimately stratified societies, these large scale changes must be reconciled with evidence of technological organization and exchange. While a skeleton of expectations can be built from the general anthropological evidence provided in this chapter, the regional specifics of Andean prehistory flesh out the character of production and exchange of Chivay obsidian through time. Models that are applicable to the case of Chivay obsidian and that assimilate issues from this chapter with the Andean regional trajectory are presented at the end of the following chapter.