2.2.4. Definitions of exchange

Studies of exchange can contribute to understanding human behavior because, more than any other species, humans have possessions and shift them between individuals. A person can acquire an object of wealth either by producing it or exchanging for it. In the terms used by economic anthropologists, exchange takes a number of forms in social interaction. Wealth is the objective of a person's labor and is therefore culturally determined. Markets refers to a market-based economy where prices reflect supply and demand (LaLone 1982: 300), as is not to be confused with aggregated transfers of various forms occurring in marketplaces. Exchange or trade are commonly used terms for processes referred to more generally by economists as transfer or allocation (Hunt 2002). Commodities, goods, and products are used here synonymously here and do not imply exchangeability or alienability.

Polanyi and the economics of exchange

The principal forms of economic organization outlined by Karl Polanyi (1957) - reciprocity, redistribution, and market forces - have been widely used in anthropological discussions of exchange. Paul Bohannan describes the relevance of these economic modes to exchange:

Reciprocity involves exchange of goods between people who are bound in non-market, non-hierarchical relationships to one another. The exchange does not create the relationship, but rather is part of the behavior that gives it context.

Redistribution is defined by Polanyi as a systematic movement of goods towards an administrative center and their reallotment by the authorities at the center.

Market Exchange is the exchange of goods at prices determined by the law of supply and demand. Its essence is free and casual contract (Bohannan 1965: 232).

In principle, the price-fixing aspect of market based exchange has an integrative effect and entails communication between segments of the exchange sphere. For the trader, market exchange involves risk and potential profit. For the producer, the consumption patterns and fluctuations in demand should be sensed all the way back in the contexts of production. Market articulation in land-locked regions of Asia and North Africa provided the initial contexts for large-scale caravans in the Old World. With caravans perennially under threat of robbery or obligation to pay duties for crossing sovereign land, the "nomadic empires of the Turk, Mongol, Arabic, and Berber peoples were spread out like nets alongside transcontinental caravan routes" (Polanyi 1975: 146-149). In contrast to market mechanisms, Polanyi also described exchange modes of institutional or administered trade, where material needs were satisfied through the movement of goods but the practice was not motivated by "profit" for merchants in the market sense of the term but rather to meet institutional goals (Salomon 1985: 516;Stanish 1992: 14;Valensi 1981: 5-6). In this type of trade, value and equivalencies are established by political authority or by precedent.

Characteristics of a market economy

Markets are of particular interest in this discussion because while market principles, to a certain extent, underlie all formal economic approaches in anthropology, market-based economies are far from universal in the premodern world, even among state-level societies. A basic definition of a market is "the situation or context in which a supply crowd (sellers) and a demand crowd (buyers) meet to exchange goods and services" and where the market principle is operating (Dalton 1961: 1-2). Three characteristics used by Earle to evaluate the evidence for market-based exchange in the Inka state include: (1) The importance of specialized institutions of production and exchange divorced in their operations from other institutional relationships; (2) The development of a medium of exchange to facilitate the systematization of exchange values; (3) The percentage of goods utilized by a household that are obtained by exchange (Earle 1985: 372-373).

The presence of exchange institutions, either as bustling marketplaces or distributed as "site-free" exchange houses, have a characteristic described by Earle (1985: 373) as a context where "non-exchange relationships, such as kinship and political ties, will not unduly constrain choice". The alienability of products, the strong influence of price motive and the detachment from production and other social linkages, underlie many of the features of these proposed institutions. The consensus among Andeanists is that during Inka domination, and probably during the preceding periods, market-based economies were not found in the central and southern Andes with a few exceptions (Earle 2001;LaLone 1982; but see href="/biblio/ref_2005">Salomon 1986;Stanish 2003).

The location of transfer becomes important with respect to price-fixing markets. In aggregations the public nature of the contact and the circulation of information is quite different from isolated exchanges. These issues are linked to the spatial and temporal configuration of exchange in market economies because just as periodic gatherings, central places, and rank-size geographic relationships serve to distribute goods in some settlement systems, these aggregations serve to distribution information about availability of products and changing prices to buyers and sellers (Smith 1976;Smith 1976). When exchange takes place in a private courtyard rather than a public marketplace then there is reduced risk of the neighbor overhearing the barter exchange value offered to another (Blanton 1998;Humphrey and Hugh-Jones 1992). Greater public visibility and monitoring in market contexts might be expected, and greater privacy, interpersonal negotiation, and temporal depth to exchange relationships in private barter exchange configurations.

Variations on Modes of Exchange

Some scholars have built on Polanyi's four original modes of exchange, others have developed entirely new schema (Smith 1976). Earle (1977: 213-216) argues that Polanyi's (1957: 250) definition of redistribution as "appropriational movements towards a center and out of it again..." is vague and Earle observes that this definition is so broad that it could to apply to economic systems ranging from central storage of goods in Babylonia to meat distribution in band-level hunters. Earle advocates separating leveling mechanisms from institutional mechanisms, where institutionalized redistribution involves wealth accumulation and political transmission between elites across broad regions in the mode of peer-polity interaction (Earle 1997).

Andean political economy

Stanish (2003: 21) expands on Polanyi's system by describing political economy in the prehispanic Andes with deferred reciprocity taking the form of competitive feasting and political support (Hayden 1995;Stanish 2003: 21). Stanish observes that while there was an implicit or explicit (Service 1975) evolutionary sequence going from reciprocity to redistribution and finally to markets, more recent evidence suggests that these modes can co-occur and that the relationships are too complex to collapse into a single sequence.

Types of reciprocity

Sahlins (1972: 194-195) further elaborated on aspects of Polanyi's reciprocal mode with generalized, negative, and balanced reciprocity. Generalized and negative reciprocity are opposite ends of a continuum (see Figure 2-1, above). Generalized reciprocity refers to sharing, altruism, and Malinowski's "pure gift", while negative reciprocity is the attempt to maximize personal gain from the transaction through haggling or theft (Sahlins 1972: 195-196). Polanyi's basic modes of exchange have persisted in economic anthropology for almost fifty years. Some argue that Polanyi's modes of exchange are limiting in that they do not provide a means to analyze precapitalist commercial activity (Smith 2004: 84), however the benefit to Polanyi's exchange modes is that they are sufficiently general to be comparable cross-culturally and the three modes are discrete enough to be, in some cases, archaeologically distinguishable. Furthermore, if commercial activity is unlikely in the study region, as in the prehispanic south-central Andes, Polanyi's modes capture the necessarily economic variability.

Geographical characteristics

Renfrew (1975) considers trade as interaction between communities in terms of both energy and information exchange. Renfrew (1975: 8) tabulated Polanyi's schema as follows

|

Configuration |

Geographical |

Affiliation |

Solidarity |

|

|

Reciprocity: |

Symmetry |

No Central Place |

Independence |

Mechanical |

|

Redistribution: |

Centricity |

Central Place |

Central Organization |

Organic |

Table 2-3. Characteristics of reciprocity and redistribution (from Renfrew 1975: 8).

Renfrew follows with an exploration of the greater efficiency implied by central place organization in terms of material and information exchange. The universality of central place organization in the development of complex political organization worldwide has been called into question in pastoral settings. In the south-central Andes, anthropologists have proposed that alterative paths to complex social organization could have been pursued by distributed communities linked by camelid caravans with the anticipated central place hierarchy not occurring until relatively late, as proposed by Dillehay and Nuñez (1988) and in a different form by Browman (1981).

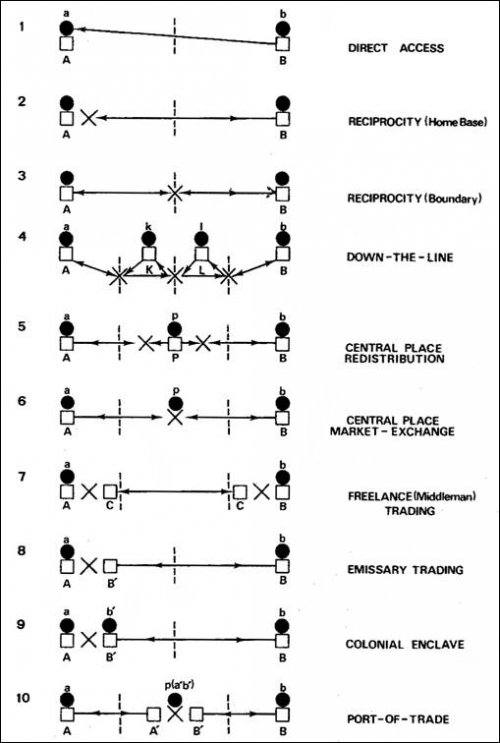

Renfrew has developed a graphical representation of the spatial relationships implied by each mode of exchange.

Figure 2-2. Modes of exchange from Renfrew (1975:520) showing human agents as squares, commodities as circles, exchange as an 'X', and boundaries as a dashed line.

The exchange modes depicted by Renfrew (1975:520), shown in Figure 2-2, efficiently convey the variety in organization represented by exchange relationships. In some regions of the world, such as the prehispanic south-central Andes, market-based economies are not believed to have operated which modifies one's expectations for the activities of traders. The full suite of these ten modes is not expected in any one particular archaeological context worldwide, but the figure serves to underscore the complexity of isolating particular types of exchange based on archaeological evidence. Furthermore, these modes are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as some of these modes may have been operating simultaneously unless restrictions on production, circulation, or consumption of goods were in place.

Exchange network structures

Based on geographer Peter Haggett's (1966) work, network configurations can be used to describe the characteristics of interaction that resulted in the distribution and circulation of goods. In describing Andean caravan transport, Nielsen (2000: 73-74, 91) uses the following terms: (1) distance that goods are transported; (2) segmentary vs. continuous - in segmentary networks a given node is connected to a small number of other nodes, while continuous networks each node is connected to all other nodes; (3) convergent (focalized) vs. divergent (non-focalized) - in convergent networks the individuals participating in exchange, and the goods they transport, tend to concentrate in a small number of central places or exchange locales.

Reciprocal exchange relationships that take the form of down-the-line trade may be described as continuous networks when these mechanisms serve to move goods between ethnic groups and across regions. Centralized political control by elites and true market mechanisms might result in network convergence at central places (Smith 1976). To Nielsen's third set of terms, convergent (focalized), divergent (non-focalized), one may add diffusive to describe the pattern of a single type of item radiating from the center to the surrounding region as occurs with obsidian.

Figure 2-3. Network configurations.

These network configurations serve to draw attention to the limitations of using raw material distributions as a proxy for all exchange behaviors. Obsidian exchange is sometimes used by archaeologists as gauge of the volume, frequency, and structure of prehistoric exchange relationships. As noted by Clark (2003), raw materials from geological sources diffuse continuously from a single point to the region, presumably following trade routes, until the materials are found deposited at archaeological consumption sites. In contrast, much exchange between complementary groups, such as between agriculturalists and pastoralists, is non-focalized and often segmentary, as it links producers and consumers through a variety of localized articulation methods. The structural differences between diffusive exchange networks and regular, household-level interaction are well demonstrated in mountain regions with distinct ecological zonation, such as the Andes.

Archaeological inferences that do not differentiate the expectations of one network configuration from another are problematic. Often, diffusive configurations will have evidence of the transport of goods in the opposite direction, as one might expect in system where obsidian is acquired through reciprocity-based relationships. However, the pattern where goods are reciprocated to the source area is a configuration model to be tested rather than one that can be assumed.